Flux, Redux, and SwiftUI

Before we dive into some code, it’s important to begin with some background, philosophy, and history. What did product engineering look like for the Apple Ecosystem before SwiftUI? How did other declarative UI frameworks and ecosystems manage shared mutable state at scale? What could we learn from other ecosystems that could influence how we think about our shared mutable state when building products for SwiftUI? It’s important to understand that the architecture we are proposing was not built in a vacuum. The code itself will be new, but the ideas behind the code have already proven themselves in the real world.

React

Facebook launched in 2004.1 By 2010, FB had grown to 500 million users.2 The previous year, FB reached another important milestone: profitability.3 To understand more the scale that engineers were shipping impact at during this era, FB was employing less than 500 engineers.

Historically, FB hired engineers as software generalists. Engineers were onboarded without being preallocated into one specific team or role. After onboarding, engineers quickly discovered that nothing was ever “complete” at FB. The company and products grew so quickly, engineers were encouraged — and were needed — to work on new products outside their speciality.

As FB (the company and the product) scaled, engineers building for front-end WWW began to realize their architecture was not scaling with them. At this point in time, FB front-end architecture was built on “classic” front-end engineering. Engineers used imperative logic to manipulate long-lived mutable view objects. Sometimes this was called “MVC”, sometimes it was called “MVVM”, and sometimes it was called “MVW” (Model-View-Whatever) or “Model-View-Asterisk”. These architectures all shared a common assumption that made it challenging to onboard new engineers and ship products at scale: views were mutable objects and engineers needed to use complex imperative logic to manage their state correctly.

Starting around 2011, a FB engineer named Jordan Walke began to “rethink best practices” about application architecture for front-end engineering. This new framework would become ReactJS. React gave engineers the tools to declare their view component tree without the need for imperative mutations directly on mutable view objects. React gave product engineers the tools to focus on “the what not the how”. For two years, FB products began to migrate to this new infra. React led to code that was faster to write and easier to maintain. After crossing the threshold of one-billion users in 2012,4 FB announced the ReactJS framework would be released to the community as open source in 2013.5

The early public demos of React gave engineers a battle-tested infra for declaring their user interface, but FB did not publicly make a strong value statement about how these engineers should manage shared mutable state at scale. While a declarative framework like React redefines the “Controller-View” relationship, React — as announced to the public — did not yet have a strong opinion about how to redefine the “Model-Controller” relationship.

Flux

What engineers outside FB did not know was that FB did have a new application architecture being developed internally alongside the React infra. During the two years React was being developed and scaled, a team of FB engineers led by Jing Chen also noticed that their architecture was not scaling as the company was growing. React focused its attention on redefining the programming model engineers use to build graphs of view components; this new team of engineers began to think about their data and their models with a similar philosophy.

At this time, conventional architectures were encouraging complex mutable state to be delivered to views through mutable objects: controllers or view models. Views were using imperative logic to mutate shared state directly: through a controller or on the model objects themselves. As the size of the product grew, the graph of relationships between controllers and models grew quadratically: it was out of control. One controller class would become so large it was slowing down engineers that needed to work on it. A temporary solution might have been to break this apart into “child” controllers, but the relationship graph between these controllers then grew quadratically. There was always going to be quadratic complexity; trying to refactor it out of one place just moved it somewhere else.

In addition, mutable model objects — where the state of these models could be directly mutated with imperative logic by the view objects — led to code that was difficult to reason about; as the size of the product scaled, engineers needed to know “global” context to make “local” changes. It was very easy for bugs to ship; an engineer might mutate state at some place in the view graph when another place in the view graph was not expecting, or prepared for, a mutation.

The next problem was bugs that looked like “race conditions” or “non-deterministic” chain reactions. Since mutable state was often being bound with two-directional data bindings that can both read from and write to an object, an engineer might mutate shared state in one part of their view graph, while a different part of the view graph is not only subscribing to listen for state mutations, but then making their own state mutations once they received that notification.

Code was complex, unpredictable, and difficult to make changes to. Parallel to the work the React team was doing to redefine the programming model product engineers used to build user interfaces, this new team began to redefine the programming model product engineers used to manage shared mutable state.

The architecture was called Flux, and shared a lot of philosophy with React. Flux gave product engineers tools to think about shared mutable state by moving away from an imperative programming model. Product engineers could declare actions and events as they happen from their view components and migrate the imperative logic to mutate state down into their model layer in Flux Stores. Product engineers no longer needed two-directional data bindings that read and wrote to shared state; the data flow became one-directional. Complex view controllers — or complex graphs of view controllers — started to become obsolete. Code became simple, predictable, and easy to make changes to.

Flux was built on JS, but drew a lot of influence from Haskell, a functional programming language, and Ruby, a “multi-paradigm” language (like JavaScript) that also encouraged functional programming patterns. Another influence was the Command Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS) Pattern.6

Conceptually and ideologically, Flux paired very well with the programming model of React. In 2014, one year after React was announced, FB announced the Flux architecture.7 While Flux did ship with a small JS framework library, product engineers outside FB were encouraged to think about Flux as a design pattern that could also be implemented with custom frameworks. While the first public releases of React shipped without a strong opinion about an architecture for state management, FB was now evangelizing Flux as the correct “default” choice for most product engineers coming to the React Ecosystem.

ComponentKit

While front-end engineering for WWW was undergoing big changes at FB, mobile engineering for iOS was also evolving in new directions. From the early days of engineering at FB, the company was first and foremost a “web” company. The DNA of the company was very much tied into the WWW product and ecosystem. In an attempt to share engineering resources and knowledge, the FB “Big Blue” mobile app for iOS began to ship with many surfaces rendered in HTML5; it was a “hybrid app”. As the app began to grow (more products and more users), the performance limitations of HTML5 were impacting the reputation of the business: users were complaining. About the time WWW engineers were beginning to build React, FB engineers started to build a new version of the native mobile app for iOS.

As FB transitioned away from HTML5 hybrid views, engineers made some architectural decisions that would have important consequences later. FB mobile engineers chose MVC and UIKit as their main architecture. To manage their shared mutable state and data, mobile engineers chose the Core Data framework. The first native rewrites to the Big Blue FB app were successful: performance was much better than the hybrid app. This same year, FB publicly announced it was focusing on “mobile-first” growth.8 Historically, engineers at FB might launch new features on WWW. Launching that same feature on mobile iOS either meant writing HTML5 in a hybrid app, or waiting for one of the (few) native specialists at the company to build native Objective-C and UIKit.

With FB focusing on mobile-first growth, engineers from across the company that were shipping new products were now ramping up on learning UIKit and Core Data to ship on this new technology. Everything was good… until it wasn’t.

When the engineers building the native rewrite chose MVC, UIKit, and Core Data, the engineers were choosing what looked like the “best practices” at the time. These were the tools Apple built, and these were the tools Apple told engineers were the best for building applications at scale. While building an application using “conventional” iOS architecture and frameworks might have helped FB move fast and ship quickly, this architecture would soon lead to the same class of problems that caused the WWW team to pivot to React and Flux.

When placing and updating views on screen, the imperative and object-oriented programming model of UIKit and MVC was slowing engineers down. View Controllers were growing at quadratic complexity as the product scaled. Controllers — either one giant controller or a complex graph of controllers — would need to correctly position and mutate a graph of view objects using imperative logic. It was very easy for engineers to make a mistake that led to UI bugs and glitches. As this was happening, the Core Data framework was locking engineers into thinking about data as mutable model objects which were updated using imperative logic. Two-directional data bindings on these mutable model objects were leading to the same “cascading” class of bugs the front-end WWW team saw before Flux. On top of that, Core Data was really slow. Engineers tried all the tricks they could think of to speed up Core Data, but it led to unnecessary complexity that product engineers would have to work through and understand.

Neither of these frameworks (UIKit or Core Data) were scaling to support the ambitious goals of FB continuing to ship products with mobile-first growth. After about two years of struggling with MVC, a team of engineers led by Adam Ernst began an ambitious attempt to “rewrite” the app that had already been rewritten only two years before. They saw that the front-end WWW team encountered problems scaling products built on a MVC architecture, and the native mobile team was encountering the same class of problems. They saw that migrating to React and Flux solved these problems for WWW engineers, and they began to write an Objective-C++ native version of the React and Flux frameworks. These new frameworks, like React and Flux, would encourage declarative thinking instead of imperative thinking, functional programming instead of object-oriented programming, and immutable model values instead of mutable model objects.

The new UI framework was called ComponentKit.9 ComponentKit originally launched as a rewrite of the News Feed product, but ComponentKit spread to become the dominant framework product engineers would use for mobile iOS at FB. While ComponentKit was using the principles of React to solve the scalability problems of UI layout by migrating away from UIKit, a project called MemModels was in development to use the principles of Flux to solve the scalability problems of mutable state management by migrating away from Core Data. ComponentKit was released to the open-source community in 2015, but the “native” Flux framework was unfortunately not released publicly. Similar to the first version of React, FB presented a solution for bringing declarative programming to UI product engineering, but did not ship a companion framework for bringing declarative programming to complex state management.

Redux

The Flux framework and architecture was released to the open-source community in 2014. Over the following year, the engineering team behind Flux saw that product engineers at FB were beginning to repeat some of the same logic across products. Flux did not make assumptions about caching, faulting, paging, sorting, or other typical work that a network-driven application like FB might perform to fetch and present data from a remote server. For smaller companies and teams, the Flux framework might have been a great starting point for building the data model for smaller applications. For a rapidly growing company like FB, there was a lot of engineering impact that was being lost on duplicating logic across multiple product surfaces. The Flux team began to build a new framework which started with the philosophical foundation of Flux and offered new infra to help product teams working across FB that were blocked on these common problems.

The new framework was called [Relay]10, and was released along with the [GraphQL]11 data query language as a Flux-Inspired solution for managing the complex state of a network-driven application driven by a complex (but well defined) graph schema of data. The Relay framework was powerful and a huge leap forward over the initial release of Flux, but Relay was not a lightweight and general-purpose solution for state management: it was dependent on GraphQL as a schema to model data.

As FB engineers were building Relay, the React ecosystem and community continued to experiment with the Flux architecture. Over time, a number of legit grievances about decisions or ambiguity in the original Flux implementation led to the community beginning to think about what a next-generation evolution of Flux might look like.12

In 2015, Dan Abramov introduced the Redux framework and architecture at React Europe.13 For the most part, Redux began with many of the same opinions and assumptions of Flux: data still flowed in one direction with product engineers passing actions using declarative logic instead of mutating state directly at the component level with imperative logic. At the model layer, Flux Stores — which could be multiple stores in one application — contained imperative logic for mapping actions to mutations on state. Unlike Flux, Redux builds from just one store and saves engineers from managing complexity to keep multiple stores synchronized. The imperative logic to map actions to mutations on state is written outside of Stores in pure functions called Reducers. Using inspiration from Elm (a language and architecture emphasizing immutability), Redux Reducers map the state of an application with an action to produce the next state of the application.14 Using inspiration from ImmutableJS, Redux requires these state objects to be immutable — unlike Flux, which gave engineers the option to model their state with mutable objects.14

The Relay framework was a very powerful solution for managing network-driven applications built from GraphQL data schemas at scale. This project was hugely impactful inside FB and for applications built from a similar tech stack, but it was a “heavyweight” solution relative to the simplicity and flexibility of the original Flux implementation. Redux refined the original Flux implementation with ideas that reduced boilerplate and simplified state transformations. Leveraging immutable data structures led to code that was more predictable and easier to reason about. Over time, Redux became the dominant choice for unidirectional data flow state management for React Applications.15

SwiftUI

While the WWW team at FB was building the React framework in JS and the iOS team at FB was building the ComponentKit framework in Objective-C++, engineers at Apple led by Chris Lattner were building the Swift Programming Language.16 Swift brought some influences from C++ along with some influences from Objective-C. Swift also brought some influences from the functional programming patterns found in languages and ecosystems like Haskell and Ruby — which were also big influences on Flux.

One of the biggest differences between Swift and Objective-C was the flexibility and power of immutable value types. While simple C-style structs allocated on the stack were always available in Objective-C, the primary building blocks of almost all Objective-C applications were objects allocated on the heap. For an application like FB that was migrating away from the semantics of mutability, this led to workarounds like choosing Objective-C++ to improve the efficiency of creating objects and the Remodel library for adding “immutable” semantics to mutable data objects.[^17]17 Swift offered more flexibility for engineers by shipping powerful immutable value type structures along with support for mutable reference type classes. Swift Structs were far more flexible and powerful than Objective-C structs. Because Swift Structs followed value semantics, engineers were now able to “reason locally” about their code in a way that was not possible with reference semantics.18 Apple soon began to recommend structs and value semantics as the “default” choice for engineers to model their data types.19

Throughout the Objective-C era, Apple continued to evangelize MVC as the preferred application architecture for applications built from AppKit and UIKit.[^21]20 While Swift introduced powerful new abilities to encourage functional programming with immutable model values, the primary tools for building applications on Apple platforms were still AppKit and UIKit — which meant that the application architecture recommended by Apple continued to be object-oriented MVC.[^23]21

As early as 2017, rumors began to leak that Apple was building a new framework for declarative UI.22 In 2019, Apple announced SwiftUI.23 For engineers experienced with building applications in the FB ecosystem using React and ComponentKit, the programming model used by SwiftUI looked very familiar. SwiftUI “views” — similar to what React and ComponentKit called “components” — were built declaratively using immutable data structures. Rather than product engineers telling their view hierarchy how it should be built using imperative logic, product engineers started telling the SwiftUI infra what should be built using declarative logic. Like React and ComponentKit, SwiftUI encouraged product engineers to focus on “the what not the how”.

Considering the experience front-end teams from WWW and iOS had trying to scale classic MVC architectures across complex applications and large teams, a first-party solution for declarative UI built on a language that included support for immutable data values and functional programming looked like a huge leap forward for engineering on Apple Platforms. While the launch of SwiftUI offered a framework for managing graphs of view components declaratively, SwiftUI, like the early versions of React and ComponentKit, shipped without strong public opinions about what architecture should look like for mutable state management.

The early demos of SwiftUI from Apple emphasize what React Engineers would think of as “component state”.24 While Apple was encouraging a unidirectional flow of data through one subgraph of view components, we did not yet hear very clear messaging from Apple about what architecture we would use for a unidirectional flow of data across multiple subgraphs of view components. Without a clear new direction from Apple, many engineers across the community — engineers that might not have the context of what had been happening in and around FB — began to architect SwiftUI applications by using declarative logic to put view components on screen, but falling back to imperative logic on shared mutable state to transform user input into the new state of their system.25

SwiftData

In 2023, Apple launched a “next-generation” update to their Core Data framework. This new version was called SwiftData.26 SwiftData reduced some of the legacy artifacts, complex setup, and repetitive boilerplate code that was needed for many engineers using Core Data in modern Swift applications. What SwiftData did not offer product engineers was a fundamentally different programming model from what was already being offered in Core Data. When using SwiftData with SwiftUI, product engineers were still using imperative logic to mutate shared object references. The “UI” side of the application was modern and declarative, but the “Data” side of the application was still classic and imperative.

ImmutableData

As we build the ImmutableData infra and deploy the architecture to sample applications in SwiftUI, we will see how we can bring our mental model of “the what not the how” to a complete application architecture. With our experience building SwiftUI applications, we already know how to “think declaratively” for building a graph of view components; all we do now is complete the pattern across our “full stack”: UI and Data. As we build our sample applications, we will use declarative programming and a unidirectional data flow to demonstrate the same philosophies and patterns that scaled to one billion users across applications at FB and across the React ecosystem.

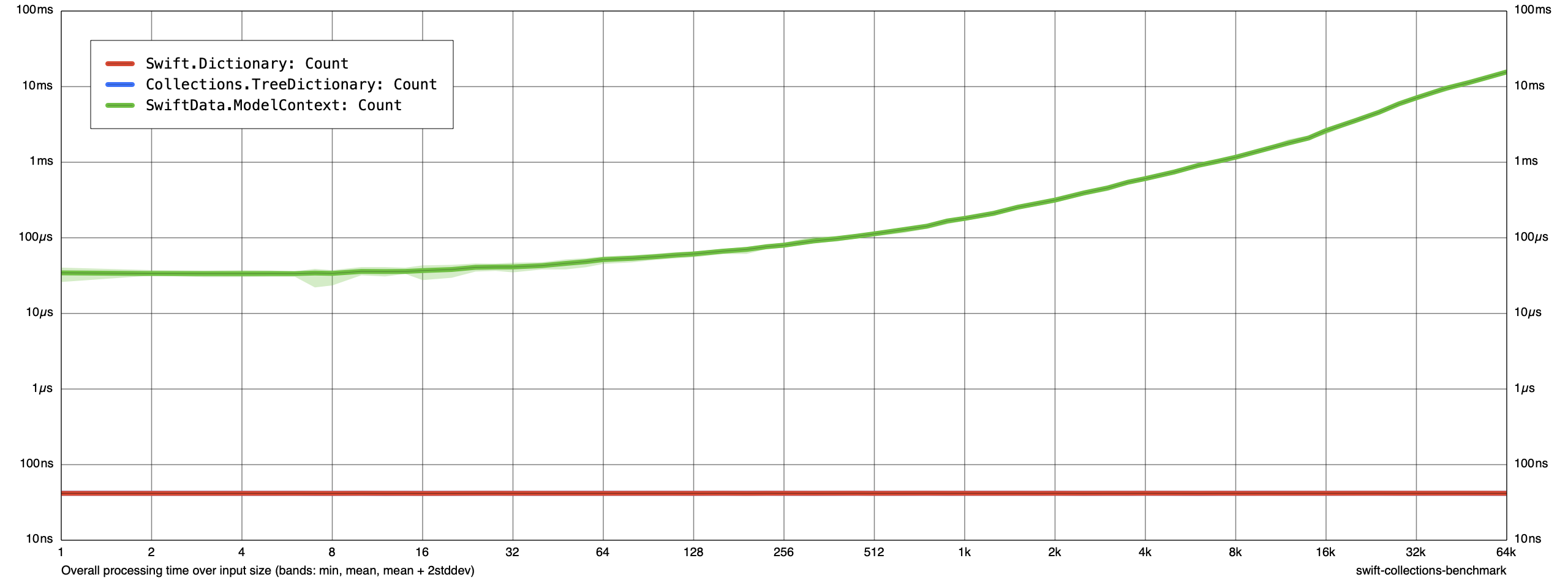

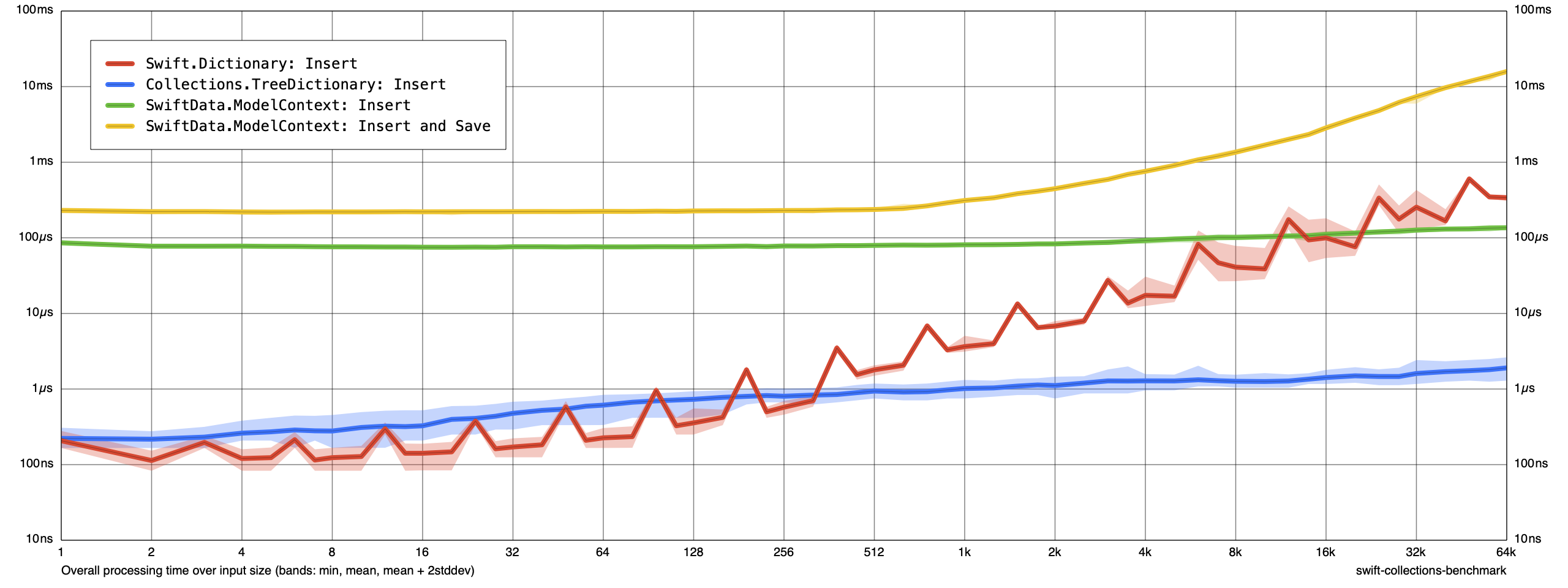

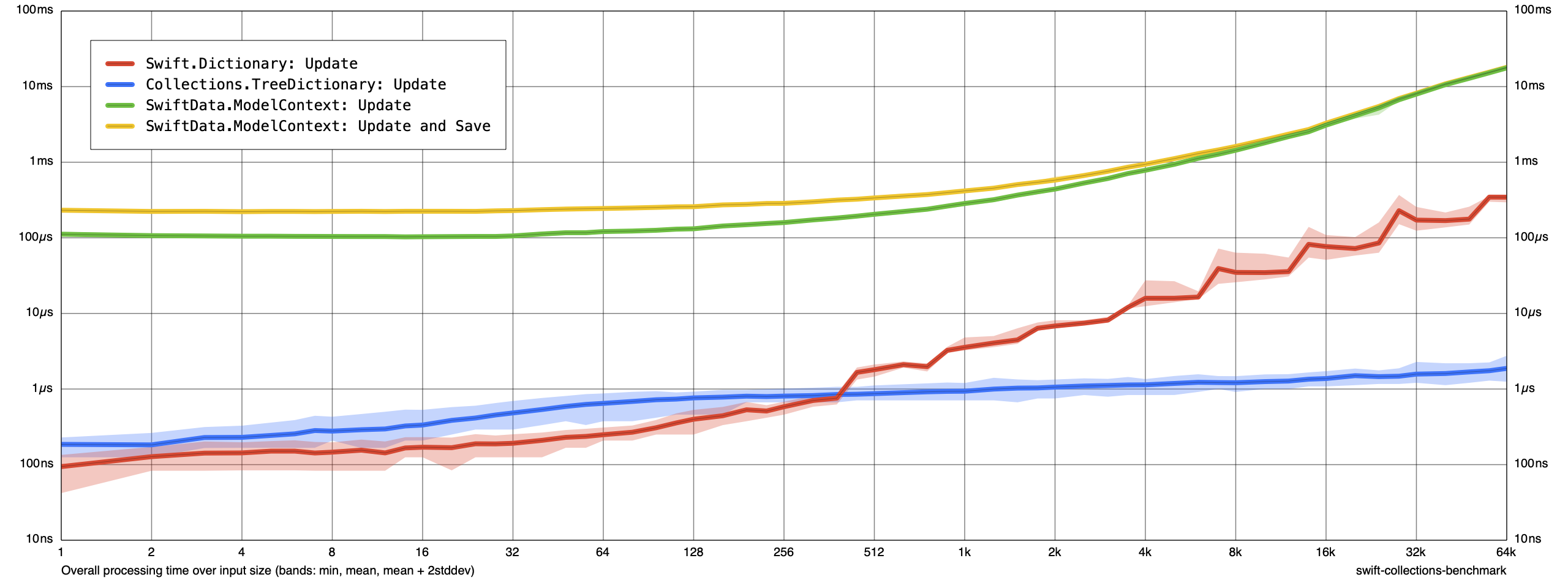

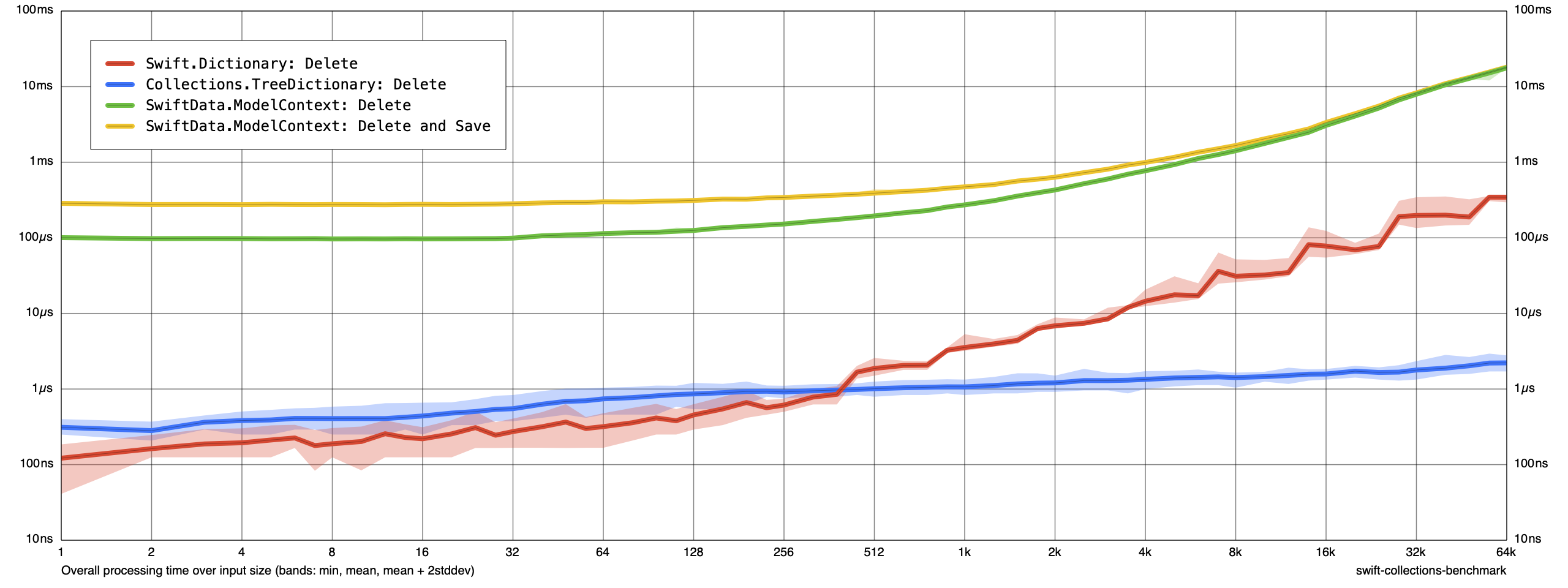

Once our applications are built and we see for ourselves what this architecture looks like, we will benchmark and measure performance. We will see how this architecture built from immutable data structures instead of SwiftData will save memory and CPU. We will even see how the ImmutableData architecture can continue to leverage SwiftData for some of its specialized behaviors: offering the improved performance and programming model of ImmutableData as a “front end” along with the efficient persistent data storage of SwiftData as a “back end”.

Migrating to ImmutableData might seem like we are asking you to “throw away” knowledge and experience, but we see a different point-of-view. We are asking you to expand the mental model you have already learned and practiced for “thinking in SwiftUI”. Bring this mental model with you as we see how declarative, functional, and immutable programming across the stack of our applications leads to code that is easy to reason about, easy to make changes to, and runs faster with less memory than SwiftData.

Let’s get started!

-

https://engineering.fb.com/2010/07/21/core-infra/scaling-facebook-to-500-million-users-and-beyond/ ↩

-

https://techcrunch.com/2009/09/15/facebook-crosses-300-million-users-oh-yeah-and-their-cash-flow-just-went-positive/ ↩

-

https://about.fb.com/news/2012/10/one-billion-people-on-facebook/ ↩

-

https://www.reuters.com/article/net-us-facebook-roadshow/facebooks-zuckerberg-says-mobile-first-priority-idUSBRE84A18520120512/ ↩

-

https://engineering.fb.com/2015/03/25/ios/introducing-componentkit-functional-and-declarative-ui-on-ios/ ↩

-

https://engineering.fb.com/2015/09/14/core-infra/relay-declarative-data-for-react-applications/ ↩

-

https://engineering.fb.com/2015/09/14/core-infra/graphql-a-data-query-language/ ↩

-

https://medium.com/@dan_abramov/the-evolution-of-flux-frameworks-6c16ad26bb31 ↩

-

https://redux.js.org/understanding/history-and-design/prior-art ↩ ↩2

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swift_(programming_language)#History ↩

-

https://engineering.fb.com/2016/04/13/ios/building-and-managing-ios-model-objects-with-remodel/ ↩

-

https://www.swift.org/documentation/articles/value-and-reference-types.html ↩

-

https://developer.apple.com/documentation/swift/choosing-between-structures-and-classes#Choose-Structures-by-Default ↩

-

https://developer.apple.com/library/archive/referencelibrary/GettingStarted/RoadMapiOS-Legacy/chapters/StreamlineYourAppswithDesignPatterns/StreamlineYourApps/StreamlineYourApps.html ↩

-

https://developer.apple.com/documentation/uikit/about_app_development_with_uikit ↩

-

https://mjtsai.com/blog/2018/05/01/scuttlebutt-regarding-apples-cross-platform-ui-project/ ↩

ImmutableData

Before we open Xcode and start working, let’s begin with a little strategy and philosophy about what we are trying to build and how we plan to build it.

This tutorial project is meant to be “hands on”: instead of giving you the infra and then showing you how to use it, we start by building the infra from scratch à la [Build Yourself a Redux]1. After building the infra together, we shift our attention to building products with that infra.

We have a few principles we want to keep in mind while engineering together:

-

We write code from scratch. There will be a few times that we present the option to import a new open-source library or external dependency, but these are for specialized tasks, like building a local HTTP server to simulate a network response, or specialized data structures for improving performance at scale. The core

ImmutableDatainfra does not require any external dependencies: it’s just you and the Apple SDK. -

We prefer simple code instead of less code. We are not optimizing for total lines of code when we work. We are optimizing for clearly communicating to engineers what this code is doing. We want to choose efficient data structures and algorithms, but we don’t look for opportunities to write “clever” code if simple code runs at the same time and space complexity.

-

Our infra should be lightweight, and the API our products use to communicate with that infra should also be lightweight. We aren’t trying to “fight the framework” with syntax or design that feels out of place with “traditional” SwiftUI applications. Our goal is to teach a new way of thinking about state management and data flow for SwiftUI. That does not mean you should have to un-learn or throw away the knowledge you already have. Most of what you already know will transfer over to this “new” way of thinking about things. You already know how to put SwiftUI on screen; what we’re teaching is a new way of getting the events out of SwiftUI and turning those events into transformations on your state.

-

Our

ImmutableDatainfra will deploy to any Apple platform that supports SwiftUI. To save ourselves some time, our sample application products will build SwiftUI optimized only for macOS. Learning how to build SwiftUI in a way that is optimized for multiple platforms is an important skill, but this is orthogonal to our goal of teaching a new way of thinking about state management and data flow. You are welcome to use our macOS sample application products as a starting point if you would like to build SwiftUI products that are also optimized for iOS, iPadOS, tvOS, visionOS, or watchOS. -

We write code that is testable, but we don’t teach you how to write tests. We like unit testing,[^2]2 but we understand that some of you might have different opinions or learning styles when it comes to engineering. Instead of teaching engineers how to build this infra and these products and the tests that go along with them, we give engineers the opportunity to write as many tests as they choose. The

mainbranch and thechapterbranches of theImmutableData-Samplesrepo contain the completed tests. You are welcome to reference our tests if you would like to see for yourself how an engineer might test a product built onImmutableData. -

This project is intended to be completed linearly: from beginning to end. You are welcome to complete every chapter at your own pace, but each chapter will build on what we learned previously. If you skip ahead, you might lose some important context or insight and the tutorial might be more challenging than we intended.

After completing this tutorial, we will have built multiple Swift Modules together. These modules are our “infra”, the shared libraries that are used to build sample applications, and our “products”, the sample applications that depend on our shared libraries. Here is what we are going to build:

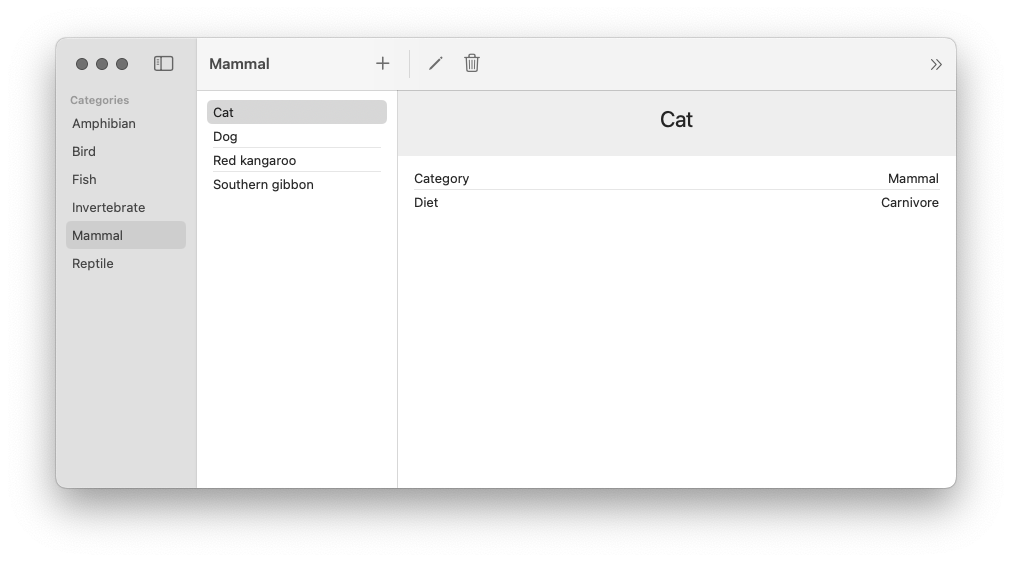

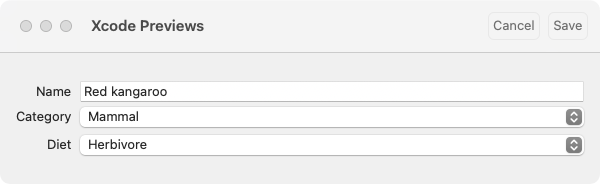

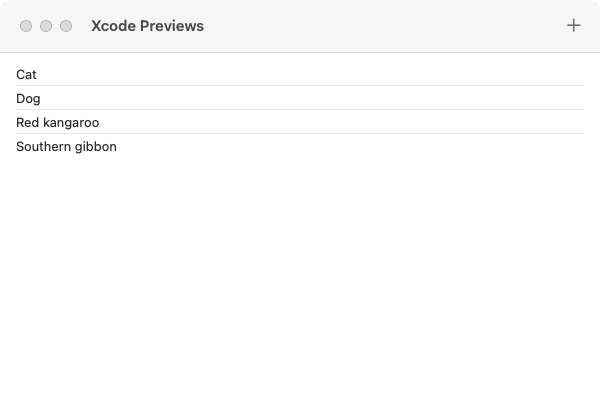

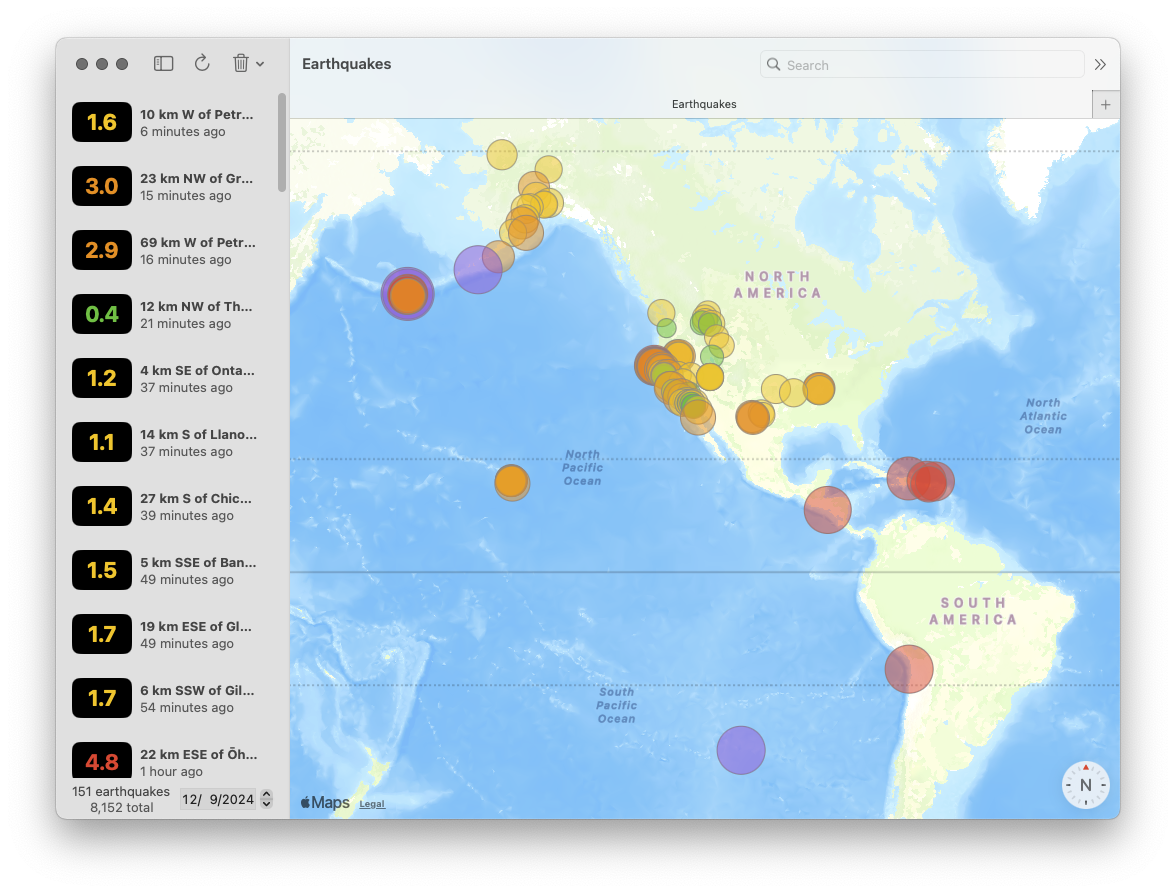

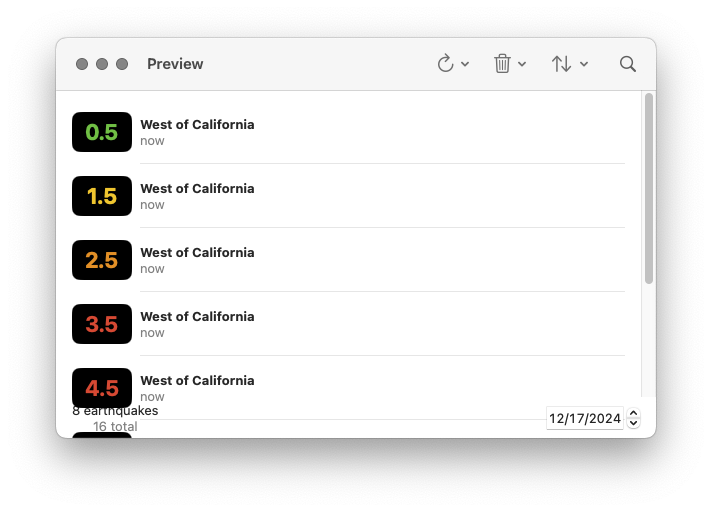

ImmutableData: This is the “data” infra module to power ourImmutableDataarchitecture. This module builds theStorewhere we save our global application state.ImmutableUI: This is the “UI” infra module that we use to read from and write to ourStorefrom SwiftUI.Counter: This is a sample application product similar to a “Hello World” for ourImmutableDataarchitecture. This application is very simple, but is good practice to see the architecture in action before we build more complex products.Animals: This is a sample application product cloning the Animals SwiftUI sample application from Apple.3 The application from Apple demonstrates how to read and write model data to a SwiftData store. We rebuild this application using theImmutableDatainfra and architecture. In addition to persisting data on disk across app launches, we also demonstrate how theImmutableDataarchitecture can read and write model data to a remote server.Quakes: This is a sample application product cloning the Quakes SwiftUI sample application from Apple.4 The application from Apple demonstrates fetching data from a remote server and caching that data locally using SwiftData. We rebuild this application using theImmutableDatainfra and architecture.

We’re almost ready to get started. The recommended approach is to clone the ImmutableData-Samples repo and checkout the chapter-00 branch. From this commit, you have the option to open Workspace.xcworkspace for a starting point to begin our engineering. The workspace is a collection of modules and application projects. To save ourselves some time and stay focused on teaching the ImmutableData architecture, these modules and application projects are already configured with the correct dependencies between each other. When it is time to add new types to a module, all we have to do is add a new file in the correct place.

Every chapter in this tutorial is focused on a different module. Think of these like a series of pair-programming sessions. Once you open the Workspace from the ImmutableData-Samples repo, we can focus our attention on the module we work through in that chapter.

Once you clone the ImmutableData-Samples repo locally, you have the option to view the completed project from the latest main commit. You also have the option to view the completed work for every chapter: the chapter-01 branch contains all the work needed to complete Chapter 01 in the book. Referencing the repo as you complete chapters also gives you the opportunity to view the complete unit tests which you have the option to use as a starting point for writing unit tests against the ImmutableData architecture in your own products.

Store

The Store class will save the current state of our data models. Our Store class is a long-lived object. You might think of a Store as behaving similar in some ways to a ModelContext from SwiftData. Unlike ModelContext, we expect applications to build just one Store instance for every app lifecycle, but you can create multiple instances when testing.

Our Store instance will be our “source of truth” for all global state in our application. This does not mean our Store instance will need to be the source of truth for ephemeral, local, or component state. Building our sample applications will give us practice choosing what state belongs in Store and what state can be saved directly in our SwiftUI component tree.

Before we write some code, let’s learn a little more about some of the basic types that we use to model and transform our global state over time. Our ImmutableData architecture is inspired by Flux and Redux. While we do not assume any prior experience with Flux and Redux before beginning this tutorial, you might want to familiarize yourself with the basic ideas behind these architectures before we build ImmutableData. We recommend [The Case for Flux]5 by Dan Abramov and [A Cartoon Intro to Redux]6 by Lin Clark to learn more.

State

Our Store class is responsible for saving a State value: this is the source of truth for all global state at a moment in time. This data model is a graph of immutable data structures: we build State by composing Swift value types like struct and enum.

flowchart LR accTitle: Data Flow in SwiftUI Part One accDescr: Our view is a function of state. State --> View

In SwiftUI, our View can be thought of as a function of State. Our components define a body property to construct a declarative description of our UI at this moment in time. It is the responsibility of the infra engineer building SwiftUI to map those declarative descriptions to View objects. When our State updates, our component recomputes our body property.

For this chapter, our State value is where we keep global state. We continue to keep local state saved directly in our component tree. Suppose we were building an application similar to the Contacts application on macOS. A Person data model might represent one person in our application. A customer opening our application would expect changes to their saved contacts to persist across app launches. A customer would also expect that opening their saved contacts in multiple windows would display the same contacts. This implies that our Person data models are what we call global state. While our customer opens their saved contacts in multiple windows, our customer has the ability to display the same contacts in different ways. One window may sort contacts by first name, another window may sort contacts by last name, and another window may filter contact names with a matching substring. These are examples of local state. This state will be saved in our SwiftUI component tree using the conventional patterns (like SwiftUI.State and SwiftUI.Binding) you are already familiar with.

When we build our sample application products, we will see how we build different State types which are customized for specific product domains. For now, our goal is to build an infra generalized across any State type; we build infra in a way that can be shared across multiple products.

Our State serves a similar role as the State type in Redux.7

Action

In a SwiftUI application using SwiftData, our data models were objects that could be mutated directly from our component tree using imperative logic. Let’s try and “think declaratively” and rebuild our mental model for mapping important events to transformations on our source of truth.

Using SwiftData, you might build a Contacts application that displays a detail component for one person. This detail component might have the ability to add or edit information on one person. You might have the ability to add or edit an email address, a phone number, or a name. These user events are then mapped at the component level to imperative instructions on the Person reference. Your “functional” and “declarative” programming model for building and updating this component tree with SwiftUI is then paired with a “object-oriented” and “imperative” programming model for building and updating your graph of data models with SwiftData.

flowchart LR accTitle: Data Flow in SwiftUI Part Two accDescr: Data flows from action to state, and from state to view. Action --> State State --> View View --> Action

In applications built from SwiftUI, we want data to flow in one direction: this helps product engineers write code that is simple, predictable, easy to reason about, and easy to make changes to. We pass our State to our Component to render a View. Our View responds to a User Event with an Action. Our Action performs a mutation on our State. Our new State then updates our Components to render a new View.

flowchart LR accTitle: Data Flow in SwiftUI Part Three accDescr: Data flows from action to state causing a mutation, and from state to view causing an update. Action -- Mutation --> State State -- Updates --> View View --> Action

Let’s think through one important step: How exactly does an Action perform a mutation on our State? The earliest public demos of React built a simple application to increment and decrement an integer value. The earliest public demos of SwiftUI built a simple application to toggle a boolean value. What these early demos have in common is that our View responds to a User Event with an imperative mutation. The product engineer building the component builds the imperative logic to mutate State directly in the component itself.

flowchart LR accTitle: Data Flow in SwiftUI Part Four accDescr: Data flows from view to state causing a mutation, and from state to view causing an update. State -- Updates --> View View -- Mutation --> State

At this point, we are leveraging a functional and declarative programming model for building and updating our component tree, but we are leveraging an object-oriented and imperative programming model for building and updating our global state.

Our approach for building the ImmutableData architecture is inspired by Flux and Redux. Instead of our component tree mutating our global state with imperative logic, our component tree declares when user events happen. At the data layer of our products, these user events then become the imperative instructions that lead to a transformation of global state.

Our user events, such as a SwiftUI button component being tapped, are instances of Action types, but Action types are not limited to user events. Action types could represent system events like a location alert when moving your device, server events like an incoming push notification or web-socket message, or other events like timers.

We model Action types as immutable data structures. Our Action types can contain context and payloads that carry information from the component tree. When thinking about Action types, try not to think about Action types as “replacements” for imperative mutations on state. An Action type declares an event that just took place; we map that event to a transformation on state using our next type.

Similar to State, we build our infra generalized across any Action type; we will see concrete examples of what Action values look like when we build our sample application products.

Our Action serves a similar role as the Action type in Redux.8

Reducer

When our Actions were imperative mutations, the product engineer building the component builds the imperative logic to mutate State directly in the component itself. When our Actions are declarative, we still need some place to define that imperative logic.

Let’s think back to our mental model for Views: our View can be thought of as a function of State. Let’s think about a similar approach for State. If we pair a State with an Action, let’s construct a function to define the imperative logic we need to transform our State.

flowchart LR accTitle: Data Flow through Reducers accDescr: Our reducer maps from a State and an Action to a new State. oldState[State] --> Reducer Action --> Reducer Reducer --> newState[State]

Our Reducer is a pure function with no side effects that maps from a State and an Action to a new State.

This is the “Fundamental Theorem of ImmutableData” and the most important concept in Redux. The job of a Reducer is to use Action values to transform State over time. Because our State is an immutable value type, we don’t mutate that State in-place; we return a new State value. Because our Reducer is a pure function with no side effects, our Reducer is deterministic, stable, and predictable.

We can now begin to visualize how the global state of our contacts application is transformed over time. We begin with a State type. This is an immutable value type. Let’s assume every Person in our contacts application is assigned a unique id property. We can then model our global state with a Dictionary where keys are the set of all id properties and values are the set of all Person values.

We can visualize a person detail component which displays the name of a Person value. Our Person is an immutable value type: unlike a SwiftData.PersistentModel, we don’t have the ability to mutate our global state with imperative logic when the user edits the name in our detail component. Instead, we forward an Action to our Reducer. Our Action tells our Reducer what just happened: “the user did tap the edit person button”. Our Action also tells our Reducer any important information like the id of the Person and new name value. With a Dictionary value as our current source of truth, our Reducer can then transform that source of truth into a new global state: a new Dictionary value.

Our product engineer will construct the actual Reducer function needed for our product domain. Our infra is generalized across any Reducer function.

Our Reducer serves a similar role as the Reducer function type in Redux.9

Store

Our State and Action types are immutable value types. Our Reducer is a pure function with no side effects. Our global state is displayed across multiple components and even multiple windows; we need a long-lived object to save a State value to represent the state of our system at a moment in time. This will be our Store class.

flowchart LR accTitle: Data Flow in ImmutableData accDescr: Data flows from action to store. The store passes the action to a reducer along with the current state of our application. The reducer transforms the current state of our application to a new state. The new state updates the view. The view creates an action on a user event and the cycle continues. Action --> Reducer subgraph Store State --> Reducer end Reducer --> View View --> Action

Here are some of the basic behaviors we want a Store class to implement:

- We want to save a State value to represent the state of our system at a moment in time.

- We want to give product engineers the ability to dispatch an Action value when an important event occurs. The current state of our system and the action are passed to a Reducer to determine the next state of our system.

- We want to give product engineers the ability to select an arbitrary slice of state at a moment in time and apply an arbitrary transformation to that slice of state.

- We want to give product and infra engineers the ability to listen as new Action values are dispatched to the

Store.

With these four behaviors, we can build a whole new architecture for delivering global state to SwiftUI. We can build an architecture that is predictable, testable, and scalable.

Our Store serves a similar role as the Store type in Redux.10

We’re ready to start engineering. Let’s open Workspace.xcworkspace and build our first type. Select the ImmutableData package and add a new Swift file under Sources/ImmutableData. Name this file Store.swift:

ImmutableData

├── Sources

│ └── ImmutableData

│ ├── ImmutableData.swift

│ └── Store.swift

└── Tests

└── ImmutableDataTests

└── ImmutableDataTests.swift

Here’s the first step to building our Store:

// Store.swift

@MainActor final public class Store<State, Action> : Sendable where State : Sendable, Action : Sendable {

private var state: State

private let reducer: @Sendable (State, Action) throws -> State

public init(

initialState state: State,

reducer: @escaping @Sendable (State, Action) throws -> State

) {

self.state = state

self.reducer = reducer

}

}

Our Store is a class with two generic type parameters: State and Action. The only constraints we make on State and Action are both types must be Sendable. Our State and Action will always be immutable value types, but we lack an easy ability to formalize this constraint in Swift 6.0.

Our UI component tree will select arbitrary slices of state to display from our Store. These operations will be synchronous and blocking. Isolating our Store to MainActor gives us an easy way to pass values to component body properties which are also isolated to MainActor.

Our Store initializer takes two parameters: a State and a Reducer. Our sample application products will use this initializer to customize their Store for their own domain. A contacts application would have a different initialState value than a photo library application. A photo library application would have a different Reducer than a contacts application. This Store class is flexible and composable; we can use the same implementation across all our sample application products without subclassing.

Dispatcher

Let’s think back to the four behaviors we wanted for our Store. We already have a type that represents the state of our system: we define state as a variable that can change over time. Let’s work on the ability to dispatch an Action when an important event occurs.

Before adding functionality to our Store class, let’s begin by defining our new function in a protocol. Add a new Swift file under Sources/ImmutableData. Name this file Dispatcher.swift.

Here is what our new Dispatcher protocol looks like to dispatch an Action when an important event occurs:

// Dispatcher.swift

public protocol Dispatcher<Action> : Sendable {

associatedtype Action : Sendable

@MainActor func dispatch(action: Action) throws

}

We can now switch back to Store and adopt this new protocol:

// Store.swift

extension Store : Dispatcher {

public func dispatch(action: Action) throws {

self.state = try self.reducer(self.state, action)

}

}

The Dispatcher protocol is at the heart of the ImmutableData architecture. This function is the “funnel” that all transformations on global state must pass through.

The dispatch(action:) function serves a similar role as the dispatch(action) function in Redux.11

Consistent with the philosophy from Redux, our Reducer functions are pure functions and free of side effects. Our Reducer functions are also synchronous and blocking. What if we did want to perform some asynchronous work or side effects along with the work our Reducer performs to transform state? How would this architecture scale to products that need to fetch data from a server or persist data to a local database?

We adopt two different approaches from Redux for managing asynchronous work and side effects: Thunks and Listeners. For now, let’s focus on Thunks; we will cover Listeners in a later section.

Suppose we build our contacts application to perform a network fetch for saved contacts from a remote server. When the remote server returns an array of contacts, we save those contacts as Person instances in our State. Our Reducer is not an appropriate place for asynchronous logic, we must perform our network fetch before we dispatch an Action value with the contacts returned by our remote server. We still would like a way to define the work to perform a network fetch together with the work to dispatch an Action when that network fetch returns. This is what we think of as a Thunk.12

Our Dispatcher currently accepts an Action. What we would like is the ability to also pass a Thunk closure. This closure could perform synchronous or asynchronous work that includes side effects that would not be appropriate for our Reducer. Here is how we define these new functions:

// Dispatcher.swift

public protocol Dispatcher<State, Action> : Sendable {

associatedtype State : Sendable

associatedtype Action : Sendable

associatedtype Dispatcher : ImmutableData.Dispatcher<Self.State, Self.Action>

associatedtype Selector : ImmutableData.Selector<Self.State>

@MainActor func dispatch(action: Action) throws

@MainActor func dispatch(thunk: @Sendable (Self.Dispatcher, Self.Selector) throws -> Void) rethrows

@MainActor func dispatch(thunk: @Sendable (Self.Dispatcher, Self.Selector) async throws -> Void) async rethrows

}

Here is how we adopt these functions in our Store:

// Store.swift

extension Store : Dispatcher {

public func dispatch(action: Action) throws {

self.state = try self.reducer(self.state, action)

}

public func dispatch(thunk: @Sendable (Store, Store) throws -> Void) rethrows {

try thunk(self, self)

}

public func dispatch(thunk: @Sendable (Store, Store) async throws -> Void) async rethrows {

try await thunk(self, self)

}

}

Our thunk closures accept two parameters: a Dispatcher and a Selector. Once we define a thunk closure, we can then select slices of state, dispatch actions, and even choose to dispatch new thunk closures.

Giving our Dispatcher the ability to accept these thunk closures is a powerful alternative to dispatching Action values, but there is a philosophical shift in our thinking taking place that will limit how and where we use this ability. One of our goals in building the ImmutableData architecture is to think declaratively from our UI component tree. Our thunk closures are units of imperative logic. We will see places in our sample application products where we do want this ability, but it will not be from our UI component tree. Our UI component tree will continue to dispatch Action values. Instead of our UI component tree telling our data layer how to behave when an important event occurs, we continue to dispatch Action values to tell our data layer when an important event occurs and what that event was. Before we finish building our Store, we will explore how Listeners will work together with Thunks to factor imperative logic out of our UI component tree.

Our dispatch(thunk:) functions serve a similar role as the Thunk middleware in Redux.13

Selector

Our state is still a private property. We have the ability to transform our State over time with our Reducer, but we also need a way for our UI component tree to select slices of state for displaying to the user. Let’s add this new function in a protocol. Add a new Swift file under Sources/ImmutableData. Name this file Selector.swift.

Here is what our Selector protocol looks like:

// Selector.swift

public protocol Selector<State> : Sendable {

associatedtype State : Sendable

@MainActor func select<T>(_ selector: @Sendable (Self.State) -> T) -> T where T : Sendable

}

Our UI component tree displays data which it “selects” from the current state of our system. This data could be an arbitrary slice of state, such as all contacts with a name beginning with an arbitrary letter. It could be a transformation of a slice of state, such as all contacts sorted by name. Our selector closure will define what data is returned from our Store.

We can now switch back to Store and adopt this new protocol:

// Store.swift

extension Store : Selector {

public func select<T>(_ selector: @Sendable (State) -> T) -> T where T : Sendable {

selector(self.state)

}

}

As a convenience, there might be times we want to return the complete state of our system with no transformation applied. Here is a convenience function that might be helpful for us:

// Selector.swift

extension Selector {

@MainActor public var state: State {

self.select { state in state }

}

}

As a best practice, we should prefer selecting only the slices of state needed for a UI component to display. Selecting more state than necessary might result in performance penalties where components evaluate their body on state transformations that do not display new data.

Our selector closures serve a similar role as Selector functions in Redux.14

Streamer

The final piece to our Store class will be the ability for product and infra engineers to listen as Action values are dispatched to our Store.

Our contacts application might launch and display an empty List component. To display Person instances in this List, we might need to perform a network fetch. While thunk closures do give us an ability for UI components to perform asynchronous work when an important event occurs, we want to think declaratively: we want to tell our data layer what just happened; not how it should transform State.

Our solution will be for our UI component tree to continue dispatching Action values to our Store. Since we don’t give our Reducer the ability to perform asynchronous work or side effects, we build asynchronous work or side effects in a Listener class. Our Listener receives Action values as they are dispatched to the Store, then has the ability to perform asynchronous work or side effects by passing a thunk closure back to the Store.

We will see examples of Listener types when we build our sample application products. For now, let’s focus on the ability to stream our updates to an arbitrary Listener. Add a new Swift file under Sources/ImmutableData. Name this file Streamer.swift.

Here is what our Streamer protocol will look like:

// Streamer.swift

public protocol Streamer<State, Action> : Sendable {

associatedtype State : Sendable

associatedtype Action : Sendable

associatedtype Stream : AsyncSequence, Sendable where Self.Stream.Element == (oldState: Self.State, action: Self.Action)

@MainActor func makeStream() -> Self.Stream

}

Our makeStream function returns an AsyncSequence. Every element returned by this AsyncSequence is a tuple with a State and an Action. When we dispatch an Action to our Store, we will pass that Action to our Reducer before we notify our Listener types with this Stream. Our Stream elements include the previous State of our system — before we returned from our Reducer — along with the Action that was dispatched. Our listeners will then have the ability to compare the previous State of our system with our current State and perform conditional logic: an example might be checking that a status value has changed from nil to pending before beginning a network fetch.

Our Streamer serves a similar role as the Listener middleware in Redux.15

Before we adopt the Streamer in our Store class, we need a helper class for creating new streams and disposing of old streams when they are no longer needed. Add a new Swift file under Sources/ImmutableData. Name this file StreamRegistrar.swift.

Here is our StreamRegistrar class:

// StreamRegistrar.swift

@MainActor final class StreamRegistrar<Element> : Sendable where Element : Sendable {

private var count = 0

private var dictionary = Dictionary<Int, AsyncStream<Element>.Continuation>()

deinit {

for continuation in self.dictionary.values {

continuation.finish()

}

}

}

extension StreamRegistrar {

func makeStream() -> AsyncStream<Element> {

self.count += 1

return self.makeStream(id: self.count)

}

}

extension StreamRegistrar {

func yield(_ element: Element) {

for continuation in self.dictionary.values {

continuation.yield(element)

}

}

}

extension StreamRegistrar {

private func makeStream(id: Int) -> AsyncStream<Element> {

let (stream, continuation) = AsyncStream.makeStream(of: Element.self)

continuation.onTermination = { [weak self] termination in

guard let self = self else { return }

Task {

await self.removeContinuation(id: id)

}

}

self.dictionary[id] = continuation

return stream

}

}

extension StreamRegistrar {

private func removeContinuation(id: Int) {

self.dictionary[id] = nil

}

}

The makeStream function returns a new AsyncStream instance and caches it in a Dictionary. The yield function passes a new Element to all cached AsyncStream instances.

One potential limitation with AsyncStream is the lack of “back pressure”.16 In situations where many actions are being dispatched to our Store very rapidly, our AsyncStream may “buffer” elements; this might lead to unexpected behavior if that buffer grows very large. One potential workaround might be to specify a BufferingPolicy when we construct our AsyncStream.17 Another potential workaround might be to use an AsyncAlgorithms.AsyncChannel, which does support back pressure.18 Since our Streamer protocol delivers a Stream as an associatedtype, we have some flexibility here if we decide to migrate our implementation away from AsyncStream in the future: our Store can deliver an AsyncChannel (or a different AsyncSequence type) and still conform to Streamer.

We can now update our Store class. Let’s begin with adding an instance of our StreamRegistrar:

// Store.swift

@MainActor final public class Store<State, Action> : Sendable where State : Sendable, Action : Sendable {

private let registrar = StreamRegistrar<(oldState: State, action: Action)>()

private var state: State

private let reducer: @Sendable (State, Action) throws -> State

public init(

initialState state: State,

reducer: @escaping @Sendable (State, Action) throws -> State

) {

self.state = state

self.reducer = reducer

}

}

We can use this registrar instance to adopt the Streamer protocol:

// Store.swift

extension Store : Streamer {

public func makeStream() -> AsyncStream<(oldState: State, action: Action)> {

self.registrar.makeStream()

}

}

The final step is to pass our State and Action to this registrar when an Action is dispatched and our Reducer has returned:

// Store.swift

extension Store : Dispatcher {

public func dispatch(action: Action) throws {

let oldState = self.state

self.state = try self.reducer(self.state, action)

self.registrar.yield((oldState: oldState, action: action))

}

public func dispatch(thunk: @Sendable (Store, Store) throws -> Void) rethrows {

try thunk(self, self)

}

public func dispatch(thunk: @Sendable (Store, Store) async throws -> Void) async rethrows {

try await thunk(self, self)

}

}

Remember that State is an immutable value: our Reducer does not have the ability to mutate this value in-place; the job of our Reducer is to return a new State value. Value semantics give us local reasoning: we know that oldState really is the “old” State of our system.

This Store class is small (only about 40 lines of code), but offers us powerful flexibility. With this Store built, we can turn our attention to our UI layer. Our next chapter will build the ability for SwiftUI components to read from and write to our shared mutable state.

Here is our ImmutableData package, including the tests available on our chapter-01 branch:

ImmutableData

├── Sources

│ └── ImmutableData

│ ├── Dispatcher.swift

│ ├── Selector.swift

│ ├── Store.swift

│ ├── StreamRegistrar.swift

│ └── Streamer.swift

└── Tests

└── ImmutableDataTests

└── StoreTests.swift

As we discussed, our tutorials are not intended to teach unit testing. We want to keep our tutorials focused on the ImmutableData architecture and products built from that architecture. We do feel that building infra and products in a way that supports testing is an important goal, but we let our readers choose to write their own tests to accompany the tutorials.

When you checkout our chapter-01 branch, you can see the completed work for this chapter. We also include unit tests. You have the option to review our tests; you can also checkout every chapter branch to see the tests we choose to include for every chapter of our tutorials.

-

https://developer.apple.com/documentation/swiftdata/adding-and-editing-persistent-data-in-your-app ↩

-

https://developer.apple.com/documentation/swiftdata/maintaining-a-local-copy-of-server-data ↩

-

https://medium.com/code-cartoons/a-cartoon-intro-to-redux-3afb775501a6 ↩

-

https://redux.js.org/understanding/thinking-in-redux/glossary#state ↩

-

https://redux.js.org/understanding/thinking-in-redux/glossary#action ↩

-

https://redux.js.org/understanding/thinking-in-redux/glossary#reducer ↩

-

https://redux.js.org/understanding/thinking-in-redux/glossary#store ↩

-

https://redux.js.org/usage/deriving-data-selectors#calculating-derived-data-with-selectors ↩

-

https://redux.js.org/usage/side-effects-approaches#listeners ↩

-

https://github.com/swiftlang/swift-evolution/blob/main/proposals/0406-async-stream-backpressure.md ↩

-

https://developer.apple.com/documentation/swift/asyncstream/continuation/bufferingpolicy ↩

-

https://github.com/apple/swift-async-algorithms/blob/main/Sources/AsyncAlgorithms/AsyncAlgorithms.docc/Guides/Channel.md ↩

ImmutableUI

Now that we have our Store class for saving the state of our system at a moment in time, we want a set of types to support selecting and transforming that state from SwiftUI view components.

There are three types we focus our effort on for this chapter:

Provider: A SwiftUI view component for passing aStoreinstance through a view component tree.Dispatcher: A SwiftUIDynamicPropertyfor dispatching Action values from a SwiftUI view component.Selector: A SwiftUIDynamicPropertyfor selecting a slice of State from a SwiftUI view component.

Provider

If you have experience with shipping SwiftData in a SwiftUI application, you might be familiar with the modelContext environment value.1 A typical SwiftUI application might initialize a ModelContext instance at app launch, and then make that ModelContext available through the view component tree with SwiftUI.Environment.

SwiftData supports creating multiple ModelContext instances over your app lifecycle. The Flux architecture supported multiple Store instances. We choose an approach consistent with the Redux architecture; we will create just one Store instance at app launch. We then make that Store available through the view component tree with SwiftUI.Environment.

Select the ImmutableUI package and add a new Swift file under Sources/ImmutableUI. Name this file Provider.swift. This view component is not very complex; here is all we need:

// Provider.swift

import SwiftUI

@MainActor public struct Provider<Store, Content> where Content : View {

private let keyPath: WritableKeyPath<EnvironmentValues, Store>

private let store: Store

private let content: Content

public init(

_ keyPath: WritableKeyPath<EnvironmentValues, Store>,

_ store: Store,

@ViewBuilder content: () -> Content

) {

self.keyPath = keyPath

self.store = store

self.content = content()

}

}

extension Provider : View {

public var body: some View {

self.content.environment(self.keyPath, self.store)

}

}

Our initializer takes three parameters:

- A

keyPathwhere we save ourstoreinstance. - A

storeinstance of a genericStoretype. - A

contentclosure to build aContentview component.

All we have to do when computing our body is set the environment value for keyPath to our store on the content view component tree. This store will then be available to use across that view component tree similar to modelContext.

Our Provider component serves a similar role as the Provider component in React Redux.2

Dispatcher

Now that we have the ability to pass a Store type through our environment, how do we dispatch an action from a SwiftUI view component when an important event occurs? Add a new Swift file under Sources/ImmutableUI. Name this file Dispatcher.swift.

This is a simple SwiftUI DynamicProperty. Here is all we need:

// Dispatcher.swift

import ImmutableData

import SwiftUI

@MainActor @propertyWrapper public struct Dispatcher<Store> : DynamicProperty where Store : ImmutableData.Dispatcher {

@Environment private var store: Store

public init(_ keyPath: WritableKeyPath<EnvironmentValues, Store>) {

self._store = Environment(keyPath)

}

public var wrappedValue: some ImmutableData.Dispatcher<Store.State, Store.Action> {

self.store

}

}

We initialize our Dispatcher property wrapper with a keyPath. This keyPath should match the keyPath we use to initialize our Provider component. When our SwiftUI view component is ready to dispatch an Action value, the wrappedValue property returns an opaque ImmutableData.Dispatcher. We could return the store instance as a wrappedValue of the Store type, but we are then “leaking” unnecessary information about the store that our view component does not need to know about; this approach keeps our Dispatcher focused only on dispatching Action values.

Our Dispatcher type serves a similar role as the useDispatch hook from React Redux.3

Selector

Our Provider and Dispatcher were both quick to build. Our Selector type will be more complex. Before we start looking at code, let’s talk about our strategy and goals with this type.

We want our Selector to select a slice of our State and apply an arbitrary transform. For a contacts application, an example might be to return the count of all Person values. Another example might be to select all Person values and filter for names with a matching substring. Another example might be to select all Person values and sort by name.

Let’s begin with a definition:

- We define an Output Selector that takes a State as input and returns some data as an Output.

Since we expect our global state to transform many times over an application lifecycle, we would like for this Selector to rerun its Output Selector when the output might have changed. Since the only way for our ImmutableData architecture to transform State is from dispatching an Action, one strategy would be for our Selector to rerun its Output Selector every time an Action value is dispatched to the Store. Let’s think about the performance impact of this strategy.

Let’s start with a simple example: we plan to build a SwiftUI view component that displays the total number of people in our contacts application. If our Person instances are saved as values of a Dictionary, it is trivial for us to select the count of all Person instances. This operation is constant time: O(1).

Here’s our next example: we plan to build a SwiftUI view component that filters for contact names with a matching substring. We can model this as an Output Selector that performs an amount of work linear with the amount of Person instances in our Dictionary: O(n).

Here’s our next example: we plan to build a SwiftUI view component that sorts all contacts by name. We can model this Output Selector as an O(n log n) operation.

The operations that run in O(n) and O(n log n) are not trivial; let’s think about how we can try and optimize this work. Let’s think about the sorting operation. This operation runs in O(n log n) time. However, we can think of a way to help keep this operation from running more times than necessary. Suppose we run the sort algorithm at time T(0) across all Person instances. Suppose an Action is then dispatched to the Store at time T(1). Should we then rerun the sort algorithm? Let’s think about this sort algorithm in terms of inputs and outputs. The input is a collection of Person instances. The output is a sorted array of Person instances. If this sort algorithm is a pure function with no side effects, then the output is stable and deterministic; if the input to our sort algorithm at time T(0) is the same as our input at time T(1), our sorted array could not have changed. If the algorithm to determine if two inputs are equal runs in linear time (O(n)), the option to perform an equality check on our inputs might save us a lot of performance by sorting in O(n log n) only when necessary.

- We define a Dependency Selector that takes a State as input and returns some data as a Dependency.

Instead of rerunning our Output Selector on every Action that is dispatched to our Store, we can rerun our Dependency Selectors. If our Selector memoizes or caches this set of dependencies, and only reruns our Output Selector when one of those dependencies has changed, we can offer a lot of flexibility for product engineers to optimize performance.

The total set of all Action values in our application might be large, but only a small subset of those Action values might result in any mutation to our State that would cause the result of our Output Selector to ever change. If we rerun our Dependency Selectors on every Action that is dispatched, we are performing work that might be expensive (O(n) or greater) when we don’t really need to. Let’s give our Selector the ability to filter those Action values.

- We define a

Filterthat takes a State and an Action as input and returns aBoolas output indicating this State and Action should cause the Dependency Selectors to rerun.

Our Dependency Selectors and Filter are both powerful tools for product engineers to optimize performance, but we would also prefer for these to be optional. A product engineer should be able to create a Selector with no Dependency Selectors and no Filter; this would just rerun the Output Selector on every Action that is dispatched to the Store.

Now that we have some strategy written out, we can begin to build our Selector type. This will be the most complex type we have built so far, but we’ll go step-by-step and try to keep things as simple as possible.

Our Selector type serves a similar role as the useSelector hook from React Redux.4 Our use of memoization and dependency selectors serves a similar role as the Reselect library.5

Our Selector type will use the Streamer protocol we defined in our last chapter for updating our view components as our State transforms over time. There are three types we will build:

Selector: This is apublictype for view components to select a slice of State.Listener: This is apackagetype forSelectorto begin listening toStreamer.AsyncListener: This is aninternaltype forListenerto begin listening toStreamer.

Our AsyncListener is a “helper”; we could make Listener complex enough to listen to Streamer on its own, but we can keep our code a little more organized by keeping some work in AsyncListener.

Our first step is to define our DependencySelector and OutputSelector types. Add a new Swift file under Sources/ImmutableUI. Name this file Selector.swift.

Here are our first two types:

// Selector.swift

public struct DependencySelector<State, Dependency> {

let select: @Sendable (State) -> Dependency

let didChange: @Sendable (Dependency, Dependency) -> Bool

public init(

select: @escaping @Sendable (State) -> Dependency,

didChange: @escaping @Sendable (Dependency, Dependency) -> Bool

) {

self.select = select

self.didChange = didChange

}

}

public struct OutputSelector<State, Output> {

let select: @Sendable (State) -> Output

let didChange: @Sendable (Output, Output) -> Bool

public init(

select: @escaping @Sendable (State) -> Output,

didChange: @escaping @Sendable (Output, Output) -> Bool

) {

self.select = select

self.didChange = didChange

}

}

Our DependencySelector type is initialized with a select closure, which returns a Dependency from a State, and a didChange closure, which returns true when two Dependency values have changed. In practice, we expect most product engineers to choose for their Dependency type to use value inequality (!=) to indicate when two Dependency values have changed. Our approach gives this infra the flexibility to handle more advanced use cases where product engineers need specialized control over the value returned from didChange.

Our OutputSelector type follows a similar pattern: a select closure, which returns an Output from a State, and a didChange closure, which returns true when two Output values have changed. Our didChange closure will be needed when we give our type the ability to use Observable for updating our view component tree.

Let’s turn our attention to AsyncListener. Add a new Swift file under Sources/ImmutableUI. Name this file AsyncListener.swift.

Our AsyncListener will use Observable to keep our view component tree updated. For a quick review of Observable, please read [SE-0395]6. Let’s begin with a small class just for Observable:

// AsyncListener.swift

import Foundation

import ImmutableData

import Observation

@MainActor @Observable final fileprivate class Storage<Output> {

var output: Output?

}

Let’s add our AsyncListener type:

// AsyncListener.swift

@MainActor final class AsyncListener<State, Action, each Dependency, Output> where State : Sendable, Action : Sendable, repeat each Dependency : Sendable, Output : Sendable {

private let label: String?

private let filter: (@Sendable (State, Action) -> Bool)?

private let dependencySelector: (repeat DependencySelector<State, each Dependency>)

private let outputSelector: OutputSelector<State, Output>

private var oldDependency: (repeat each Dependency)?

private var oldOutput: Output?

private let storage = Storage<Output>()

init(

label: String? = nil,

filter isIncluded: (@Sendable (State, Action) -> Bool)? = nil,

dependencySelector: repeat DependencySelector<State, each Dependency>,

outputSelector: OutputSelector<State, Output>

) {

self.label = label

self.filter = isIncluded

self.dependencySelector = (repeat each dependencySelector)

self.outputSelector = outputSelector

}

}

Our AsyncListener class is generic across these types:

State: The State type defined by our product and ourStore.ActionThe Action type defined by our product and ourStore.Dependency: A parameter pack of types defined by our product.Output: A type defined by our product.

For a quick review of parameter packs and variadic types, please read [SE-0393]7 and [SE-0398]8.

Our AsyncListener class is initialized with these parameters:

label: An optionalStringused for debugging and console logging.filter: An optionalFilterclosure.dependencySelector: A parameter pack ofDependencySelectorvalues. An empty pack indicates no dependencies are needed.outputSelector: AnOutputSelectorfor displaying data in a view component.

Since we use this type for displaying data in a view component, we choose to isolate our type to MainActor.

In a future version of Swift, we might choose to make AsyncListener an Observable type and remove our Storage class. As of Swift 6.0, we are currently blocked on making a variadic type Observable; we use our Storage class as a workaround.9

Here is the function for delivering an Output value to a view component:

// AsyncListener.swift

extension AsyncListener {

var output: Output {

guard let output = self.storage.output else { fatalError("missing output") }

return output

}

}

Our Storage returns an optional output. Before we complete this chapter, we will see how we can guarantee that this will not be nil and why a fatalError is used to indicate programmer error.

Let’s add two helper functions we will use only for debugging purposes:

// AsyncListener.swift

extension UserDefaults {

fileprivate var isDebug: Bool {

self.bool(forKey: "com.northbronson.ImmutableUI.Debug")

}

}

fileprivate func address(of x: AnyObject) -> String {

var result = String(

unsafeBitCast(x, to: UInt.self),

radix: 16

)

for _ in 0..<(2 * MemoryLayout<UnsafeRawPointer>.size - result.utf16.count) {

result = "0" + result

}

return "0x" + result

}

We will need three more functions for working with our parameter pack values:

// AsyncListener.swift

extension ImmutableData.Selector {

@MainActor fileprivate func selectMany<each T>(_ select: repeat @escaping @Sendable (State) -> each T) -> (repeat each T) where repeat each T : Sendable {

(repeat self.select(each select))

}

}

fileprivate struct NotEmpty: Error {}

fileprivate func isEmpty<each Element>(_ element: repeat each Element) -> Bool {

func _isEmpty<T>(_ t: T) throws {

throw NotEmpty()

}

do {

repeat try _isEmpty(each element)

} catch {

return false

}

return true

}

fileprivate struct DidChange: Error {}

fileprivate func didChange<each Element>(

_ didChange: repeat @escaping @Sendable (each Element, each Element) -> Bool,

lhs: repeat each Element,

rhs: repeat each Element

) -> Bool {

func _didChange<T>(_ didChange: (T, T) -> Bool, _ lhs: T, _ rhs: T) throws {

if didChange(lhs, rhs) {

throw DidChange()

}

}

do {

repeat try _didChange(each didChange, each lhs, each rhs)

} catch {

return true

}

return false

}

Our original Selector protocol from the previous chapter returned a slice of State for one closure defined by our product engineer. For our DependencySelector values, a product engineer has the option to request that multiple slices of state be used to determine whether or not a dispatched Action should rerun our OutputSelector. Our selectMany function makes it easy for us to pass a parameter pack of closures and return a parameter pack of slices of State.

We include a isEmpty function for confirming if our parameter pack contains no values. We include a didChange function for confirming if two parameter packs changed. We use do-catch statements, but we could also choose for-in and leverage parameter pack iteration for this function.10

Let’s now add a function to update our cached dependency values:

// AsyncListener.swift

extension AsyncListener {

private func updateDependency(with store: some ImmutableData.Selector<State>) -> Bool {

#if DEBUG

if let label = self.label,

UserDefaults.standard.isDebug {

print("[ImmutableUI][AsyncListener]: \(address(of: self)) Update Dependency: \(label)")

}

#endif

let dependency = store.selectMany(repeat (each self.dependencySelector).select)

if let oldDependency = self.oldDependency {

self.oldDependency = dependency

return didChange(

repeat (each self.dependencySelector).didChange,

lhs: repeat each oldDependency,

rhs: repeat each dependency

)

} else {

self.oldDependency = dependency

return true

}

}

}