AnimalsData

Our Counter application was an introduction to what product engineering looks like when using the ImmutableData architecture. The application was meant to be simple; our goal for presenting this application was to begin to build the “muscle memory” for thinking declaratively.

You’ve seen one example of what ImmutableData looks like as a product engineer, but you might have some important questions about how well an architecture like this scales to complex applications. Our CounterReducer performs all its work synchronously and free of side effects. For an application that saves all of its data in-memory, this might be all we need. Many of us are going to be shipping complex products that must perform asynchronous fetching to query data from a server. Our products might need to save data to a persistent store for it to be available across app launches. These are examples of side effects that should not happen from a Reducer. Our goal for these next chapters will be to learn how to use ImmutableData for products that need to perform asynchronous work and side effects.

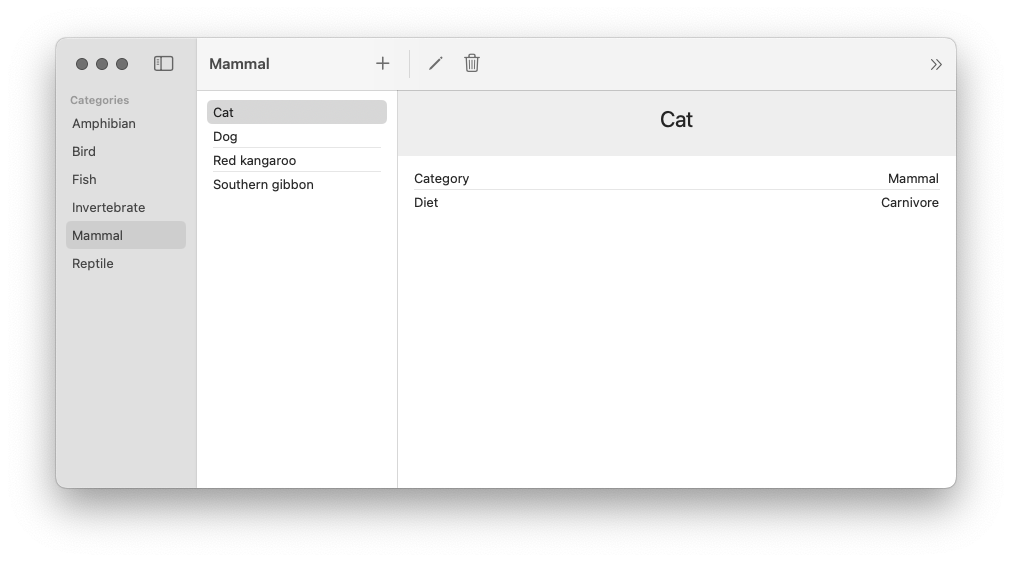

Our product will be called Animals. It is a direct clone of the Animals sample application shipped by Apple.1 Go ahead and clone the Apple project repo, build the application, and look around to see the functionality. The Apple project supports multiple platforms, but we are going to focus our attention on macOS.

Our Animals product is a catalog of animals and animal categories. The set of all animal category values is fixed, but animals can be added, deleted, and edited. Every animal comes with a name, an animal category, and a diet classification (the diet values are also fixed).

The application loads with a set of sample data. There are the six animal categories and six animals. Selecting a category from the category list displays all animals assigned to that category. Selecting an animal from the list displays an animal detail page with the data for that animal. The animal detail page displays buttons to edit or delete the animal. The toolbar also displays a button to add a new animal and a button to reload the sample data that was displayed when the app was first launched.

The Animals application leverages SwiftUI to display data and SwiftData to persist that data across app launches. Pairing SwiftUI with SwiftData is a very common pattern, so this application is a great example for us to practice using ImmutableData for these more advanced use cases.

Similar to our previous application, we will start with our data layer and our data models. This will also be the layer where we build our support for adding asynchronous side effects when we dispatch Action values to our Reducer. We build a user-interface layer that depends on that data layer to display data. Our final step will be a thin app layer that ties everything together.

Category

There are two basic data model types represented in our state: Animals and Categories. Let’s begin by adding a Category data model. Select the AnimalsData package and add a new Swift file under Sources/AnimalsData. Name this file Category.swift.

// Category.swift

public struct Category: Hashable, Sendable {

public let categoryId: String

public let name: String

package init(

categoryId: String,

name: String

) {

self.categoryId = categoryId

self.name = name

}

}

extension Category: Identifiable {

public var id: String {

self.categoryId

}

}

This type is pretty simple: just a categoryId and a name. We conform to Identifiable to indicate the categoryId value represents the unique identifier of this instance. We conform to Hashable for the ability to test for equality and create stable hash values.

Our Category is public for us to use it from different packages (like AnimalsUI). Our init is package to imply instances will only be created from this package. Packages like AnimalsUI should not have the ability to create or mutate these instances directly; we will dispatch Action values through a Reducer to affect changes in our global state.

Similar to the Apple sample project, we want to generate some sample data on the initial app launch. Here are some Category values for that:

// Category.swift

extension Category {

public static var amphibian: Self {

Self(

categoryId: "Amphibian",

name: "Amphibian"

)

}

public static var bird: Self {

Self(

categoryId: "Bird",

name: "Bird"

)

}

public static var fish: Self {

Self(

categoryId: "Fish",

name: "Fish"

)

}

public static var invertebrate: Self {

Self(

categoryId: "Invertebrate",

name: "Invertebrate"

)

}

public static var mammal: Self {

Self(

categoryId: "Mammal",

name: "Mammal"

)

}

public static var reptile: Self {

Self(

categoryId: "Reptile",

name: "Reptile"

)

}

}

Animal

Let’s add the Animal data model. Add a new Swift file under Sources/AnimalsData. Name this file Animal.swift.

// Animal.swift

public struct Animal: Hashable, Sendable {

public let animalId: String

public let name: String

public let diet: Diet

public let categoryId: String

package init(

animalId: String,

name: String,

diet: Diet,

categoryId: String

) {

self.animalId = animalId

self.name = name

self.diet = diet

self.categoryId = categoryId

}

}

extension Animal {

public enum Diet: String, CaseIterable, Hashable, Sendable {

case herbivorous = "Herbivore"

case carnivorous = "Carnivore"

case omnivorous = "Omnivore"

}

}

extension Animal: Identifiable {

public var id: String {

self.animalId

}

}

Let’s add the sample data values:

// Animal.swift

extension Animal {

public static var dog: Self {

Self(

animalId: "Dog",

name: "Dog",

diet: .carnivorous,

categoryId: "Mammal"

)

}

public static var cat: Self {

Self(

animalId: "Cat",

name: "Cat",

diet: .carnivorous,

categoryId: "Mammal"

)

}

public static var kangaroo: Self {

Self(

animalId: "Kangaroo",

name: "Red kangaroo",

diet: .herbivorous,

categoryId: "Mammal"

)

}

public static var gibbon: Self {

Self(

animalId: "Bibbon",

name: "Southern gibbon",

diet: .herbivorous,

categoryId: "Mammal"

)

}

public static var sparrow: Self {

Self(

animalId: "Sparrow",

name: "House sparrow",

diet: .omnivorous,

categoryId: "Bird"

)

}

public static var newt: Self {

Self(

animalId: "Newt",

name: "Newt",

diet: .carnivorous,

categoryId: "Amphibian"

)

}

}

Status

Our AnimalsData module will perform asynchronous operations to persist state to the filesystem in a database. When performing these asynchronous reads and writes, there are opportunities for edge-casey bugs where two different components are attempting to read from or write to the same value. To help defend against this from happening, let’s define a small Status type for marking the progress of our asynchronous operations. Add a new Swift file under Sources/AnimalsData. Name this file Status.swift.

// Status.swift

public enum Status: Hashable, Sendable {

case empty

case waiting

case success

case failure(error: String)

}

Consistent with a convention from Redux, we adopt an enum instead of an isLoading boolean value.2 This gives us more flexibility to indicate when an attempted load has succeeded or failed.

AnimalsState

Our Animal and Category types are the basic data models of our product. We still need to define a root State type which will be passed to our Reducer.

Our convention for modeling state will follow a recommended convention from Redux. We “normalize” our data models.3 We conceptualize our root state as “domains” that can be thought of similarly to tables in a database. Each domain saves its data models through key-value pairs. For our product, these slices would be Animals and Categories. Let’s see what this looks like. Add a new Swift file under Sources/AnimalsData. Name this file AnimalsState.swift.

// AnimalsState.swift

import Foundation

public struct AnimalsState: Hashable, Sendable {

package var categories: Categories

package var animals: Animals

package init(

categories: Categories,

animals: Animals

) {

self.categories = categories

self.animals = animals

}

}

extension AnimalsState {

public init() {

self.init(

categories: Categories(),

animals: Animals()

)

}

}

Our AnimalsState is public, but the animals and categories are only package. We want these properties exposed to our test target, but our component tree should not be able to directly access the raw data. Following a convention from Redux, our Selectors will expose slices of state to our component tree. Our Selectors are public, but the exact structure of that state remains an opaque implementation detail.4

Let’s add our Categories domain:

// AnimalsState.swift

extension AnimalsState {

package struct Categories: Hashable, Sendable {

package var data: Dictionary<Category.ID, Category> = [:]

package var status: Status? = nil

package init(

data: Dictionary<Category.ID, Category> = [:],

status: Status? = nil

) {

self.data = data

self.status = status

}

}

}

Our data property is a Dictionary for efficient reading and writing of Category values by a key. Our status property will be used to represent the loading status of our Category values. When an asynchronous operation to read Category values from our persistent database is taking place, this value will be waiting. When our persistent database returns data, this value will be success.

Let’s turn our attention to Animals:

// AnimalsState.swift

extension AnimalsState {

package struct Animals: Hashable, Sendable {

package var data: Dictionary<Animal.ID, Animal> = [:]

package var status: Status? = nil

package var queue: Dictionary<Animal.ID, Status> = [:]

package init(

data: Dictionary<Animal.ID, Animal> = [:],

status: Status? = nil,

queue: Dictionary<Animal.ID, Status> = [:]

) {

self.data = data

self.status = status

self.queue = queue

}

}

}

Similar to Categories, we define a data property for efficient reading and writing of Animal values by a key and a status property to represent the loading status of our Animal values. Unlike our Category value, our Animal values can be edited and deleted. To save a loading status for specific Animal values, we can define a new queue property.

These two domains are all we need to model the global state of our product. Do these two domains represent the complete state of our product? Our product offers the ability to edit and delete existing animals with a form. We also have the ability to add new animals. Does the state of this form belong in global state? Consistent with the convention from Redux, we choose to model this form data as component state.5 For additional state, we remember our “Window Test”. If our user opens two windows to see their data in two places at once, should a currently selected animal be reflected across both windows? We believe that it would be more appropriately modeled as component state; each window can track its own currently selected animal independently.

We use Dictionary values to map key values to our data models. You might have questions about the performance of this data structure when our application grows very large. Swift Collections (like Dictionary) are copy-on-write data structures; when we copy the data structure and mutate the copy, our data structure copies all n elements. In Chapter 18, we investigate how we can add external dependencies to our module and import specialized data structures for improving CPU and memory usage. In Chapter 19, we benchmark and measure the performance of immutable data structures against SwiftData. For now, we will continue working just with the Standard Library (and Dictionary).

Our next step is to define the public Selectors which select slices of state for displaying in our component tree. The sample application from Apple will be our guide: we clone the functionality. Let’s start by conceptualizing two “buckets” of Selectors: Selectors that operate on our Categories domain and Selectors that operate on our Animals domain. In more complex applications, Selectors might need to aggregate and deliver data across multiple domains all at once; we’re going to try and keep things simple for now while we are still learning.

Let’s begin with our Categories domain. Let’s think through the different operations needed to display data from our Categories domain in our component tree:

SelectCategoriesValues: TheCategoryListdisplaysCategoryvalues in sorted alphabetical order.SelectCategories: We will also define a selector to return theDictionaryof allCategoryvalues without sorting applied; we will see how these two selectors work together to improve the performance of ourCategoryListcomponent.SelectCategoriesStatus: We return the status of our most recent request to fetchCategoryvalues. We will use this to defend against some edge-casey behavior in our component tree and disable certain user events whileCategoryvalues are being fetched.SelectCategory: We return aCategoryvalue for a givenCategory.IDkey. We would also like a selector to return aCategoryvalue for a givenAnimal.IDkey: to return aMammalfor aCat.

We perform similar work for our Animals domain:

SelectAnimalsValues: TheAnimalListcomponent displaysAnimalvalues for a specificCategory.IDvalue in sorted alphabetical order.SelectAnimals: Similar toSelectCategories, we define a Selector to return theDictionaryofAnimalvalues for a specificCategory.IDvalue without sorting applied.SelectAnimalsStatus: Similar toSelectCategoriesStatus, we return the status of our most recent request to fetchAnimalvalues.SelectAnimal: We return aAnimalvalue for a givenAnimal.IDkey.SelectAnimalStatus: UnlikeCategoryvalues,Animalvalues can be edited and deleted. We track aStatusfor eachAnimal.IDvalue with an update pending. We use this value to defend against edge-casey behavior in our component tree where two windows might try to edit the sameAnimalat the same time.

These Selectors might seem a little abstract for now, but these will make more sense once we see them in action in our component tree. We could take a different approach and define these Selectors while we build our component tree. It’s a tradeoff; we prefer this approach for now to keep our focus on building the AnimalsData package before we turn our attention to our component tree.

Let’s begin with the SelectCategories Selector. This one will be one of the more simple Selectors.

// AnimalsState.swift

extension AnimalsState {

fileprivate func selectCategories() -> Dictionary<Category.ID, Category> {

self.categories.data

}

}

extension AnimalsState {

public static func selectCategories() -> @Sendable (Self) -> Dictionary<Category.ID, Category> {

{ state in state.selectCategories() }

}

}

All we need to do here is return the Dictionary representation of our Category graph. The Selector we pass to our Store instance is a static function that takes an AnimalsState instance as a parameter. As a style convention, we define a private helper on our AnimalsState instance to pair with our static Selector. You are welcome to follow this convention in your own products if it helps you keep code simple and organized.

Let’s add SelectCategoriesValues. This is a Selector for returning a sorted array of Category values. There is no “one right way” to design a function that offers sorting; for this product, we will choose an approach consistent with SwiftData.Query.6 We offer the ability to pass a KeyPath and a SortOrder.

// AnimalsState.swift

extension AnimalsState {

fileprivate func selectCategoriesValues(

sort descriptor: SortDescriptor<Category>

) -> Array<Category> {

self.categories.data.values.sorted(using: descriptor)

}

}

extension AnimalsState {

fileprivate func selectCategoriesValues(

sort keyPath: KeyPath<Category, some Comparable> & Sendable,

order: SortOrder = .forward

) -> Array<Category> {

self.selectCategoriesValues(

sort: SortDescriptor(

keyPath,

order: order

))

}

}

extension AnimalsState {

public static func selectCategoriesValues(

sort keyPath: KeyPath<Category, some Comparable> & Sendable,

order: SortOrder = .forward

) -> @Sendable (Self) -> Array<Category> {

{ state in state.selectCategoriesValues(sort: keyPath, order: order) }

}

}

Here is the SelectCategoriesStatus Selector for returning the status of our most recent fetch.

// AnimalsState.swift

extension AnimalsState {

fileprivate func selectCategoriesStatus() -> Status? {

self.categories.status

}

}

extension AnimalsState {

public static func selectCategoriesStatus() -> @Sendable (Self) -> Status? {

{state in state.selectCategoriesStatus() }

}

}

For a given Category.ID (which could be nil), we would like a Selector to return the Category value (if it exists). Here is our SelectCategory Selector:

// AnimalsState.swift

extension AnimalsState {

fileprivate func selectCategory(categoryId: Category.ID?) -> Category? {

guard

let categoryId = categoryId

else {

return nil

}

return self.categories.data[categoryId]

}

}

extension AnimalsState {

public static func selectCategory(categoryId: Category.ID?) -> @Sendable (Self) -> Category? {

{ state in state.selectCategory(categoryId: categoryId) }

}

}

Is this Selector really necessary? We already built SelectCategories to return all the Category values. Could we return all the Category values in our component tree and then choose our desired Category from that Dictionary? We could… but this could lead to performance problems. We want our component to recompute its body when the data returned by its Selectors changes. If we only care about one Category value, but our component is depending on all Category values, we are missing an opportunity to “scope” down our Selector to depend on only the data needed in that component. Our Category values are constant, but we still follow this convention because it is going to be very important for performance as we build more complex products that depend on state that changes over time.

In addition to returning the Category value for a Category.ID, we would also like an easy way to return the Category value for an Animal.ID.

// AnimalsState.swift

extension AnimalsState {

fileprivate func selectCategory(animalId: Animal.ID?) -> Category? {

guard

let animalId = animalId,

let animal = self.animals.data[animalId]

else {

return nil

}

return self.categories.data[animal.categoryId]

}

}

extension AnimalsState {

public static func selectCategory(animalId: Animal.ID?) -> @Sendable (Self) -> Category? {

{ state in state.selectCategory(animalId: animalId) }

}

}

A legit question a this point would be why we would need an extra Selector to return the Category an Animal belongs to. Why is the Category an Animal belongs to not saved on the Animal itself? One important goal and philosophy to keep in mind is that our infra and patterns for state-management are built from Immutable Data. If every Animal instance saved the Category it belongs to as a property, that Category would be an immutable struct. When multiple Animal instances belong to the same Category, those Animal instances duplicate Category values across multiple places; there is more than one “source of truth”.

In this product, Category values are constant; they do not change over time. While we could probably get away with saving Category values as properties on Animal, you could see how we would run into problems once Category values are no longer constant. When a Category value would update state, we have to update that state across more than one source of truth.

Our preference and convention for this product is to normalize our data models consistent with a convention from Redux.3 Instead of each Animal saving its Category value, each Animal saves only its Category.ID value.

Let’s turn our attention to our Animals domain. Here is our Selector for returning all Animal values belonging to a Category.ID:

// AnimalsState.swift

extension AnimalsState {

fileprivate func selectAnimals(categoryId: Category.ID?) -> Dictionary<Animal.ID, Animal> {

guard

let categoryId = categoryId

else {

return [:]

}

return self.animals.data.filter { $0.value.categoryId == categoryId }

}

}

extension AnimalsState {

public static func selectAnimals(categoryId: Category.ID?) -> @Sendable (Self) -> Dictionary<Animal.ID, Animal> {

{ state in state.selectAnimals(categoryId: categoryId) }

}

}

Our SelectAnimals selector performs a filter transformation on our data; we iterate through all our Animal values and return those that match our Category.ID. This operation is linear time. Should we be “caching” these values so we can return them in constant time? Maybe. For the most part, we follow the Redux convention that a filtered set of Animal values is derived state and does not belong stored in our Redux state.7 As we continue building our product, we will see how AnimalsFilter can help reduce the amount of times we perform this operation.

There could be times when the best option is to cache derived data. We are not opposed to this approach, but keep in mind there is going to be additional complexity now that you are potentially duplicating data across multiple sources of truth; when your data updates you are now responsible for correctly keeping that data in-sync across multiple places. Caching derived data is not always going to be the wrong tool, but we believe it should not always be the first tool you reach for.

Let’s add a Selector for returning sorted Animal values.

// AnimalsState.swift

extension AnimalsState {

fileprivate func selectAnimalsValues(categoryId: Category.ID?) -> Array<Animal> {

guard

let categoryId = categoryId

else {

return []

}

return self.animals.data.values.filter { $0.categoryId == categoryId }

}

}

extension AnimalsState {

fileprivate func selectAnimalsValues(

categoryId: Category.ID?,

sort descriptor: SortDescriptor<Animal>

) -> Array<Animal> {

self.selectAnimalsValues(categoryId: categoryId).sorted(using: descriptor)

}

}

extension AnimalsState {

fileprivate func selectAnimalsValues(

categoryId: Category.ID?,

sort keyPath: KeyPath<Animal, some Comparable> & Sendable,

order: SortOrder = .forward

) -> Array<Animal> {

self.selectAnimalsValues(

categoryId: categoryId,

sort: SortDescriptor(

keyPath,

order: order

))

}

}

extension AnimalsState {

public static func selectAnimalsValues(

categoryId: Category.ID?,

sort keyPath: KeyPath<Animal, some Comparable> & Sendable,

order: SortOrder = .forward

) -> @Sendable (Self) -> Array<Animal> {

{ state in state.selectAnimalsValues(

categoryId: categoryId,

sort: keyPath,

order: order

) }

}

}

Similar to our approach for SelectCategoriesValues, we pass a KeyPath and a SortOrder to return sorted Animal values for a Category.ID.

Similar to SelectCategoriesStatus, we define a Selector to return the status of our most recent request to fetch Animal values. We will use this value to control around any user events that might lead to edge-casey behavior if we should not be performing this event before a request has completed.

// AnimalsState.swift

extension AnimalsState {

fileprivate func selectAnimalsStatus() -> Status? {

self.animals.status

}

}

extension AnimalsState {

public static func selectAnimalsStatus() -> @Sendable (Self) -> Status? {

{state in state.selectAnimalsStatus() }

}

}

Let’s add a Selector for returning a Animal value for a given Animal.ID:

// AnimalsState.swift

extension AnimalsState {

fileprivate func selectAnimal(animalId: Animal.ID?) -> Animal? {

guard

let animalId = animalId

else {

return nil

}

return self.animals.data[animalId]

}

}

extension AnimalsState {

public static func selectAnimal(animalId: Animal.ID?) -> @Sendable (Self) -> Animal? {

{ state in state.selectAnimal(animalId: animalId) }

}

}

Our last Selector returns a Status value for a given Animal.ID. We will use this to track when an Animal value might be waiting for a mutation; this value can be used in our component tree to prevent an edit from taking place while we are already trying to edit that same Animal value from another component.

// AnimalsState.swift

extension AnimalsState {

fileprivate func selectAnimalStatus(animalId: Animal.ID?) -> Status? {

guard

let animalId = animalId

else {

return nil

}

return self.animals.queue[animalId]

}

}

extension AnimalsState {

public static func selectAnimalStatus(animalId: Animal.ID?) -> @Sendable (Self) -> Status? {

{state in state.selectAnimalStatus(animalId: animalId) }

}

}

These Selectors are public and deliver the data and state we need to display in our component tree. We wrote a lot of code, but we also learned some important things along the way that will help us when we build Selectors for more complex products.

AnimalsAction

We learned some important lessons while building CounterAction. In that chapter, our action values represented user events from our component tree. Those user events were received by our Reducer, which mapped those user events to transformations on our State. The ImmutableData architecture requires that Reducer functions are synchronous and free of side effects. Let’s see how we build Action values when our product will perform work that is asynchronous.

Let’s build and run the existing Animals sample app from Apple. Let’s run through the functionality and sketch out the user events we can document taking place from our component tree. Let’s think carefully and document only the user events that should affect our global state; events that should only affect local component state may be omitted.

- The

CategoryListcomponent displays a button to reload the sample data from first launch. - The

AnimalListcomponent allows swiping on an Animal to delete. The option to delete a selected Animal is also available from the Menu Bar. - The

AnimalDetailcomponent displays a button to delete the selected Animal. - The

AnimalEditordisplays a button to either edit an existing Animal or save a new Animal.

This is not a complete set of all user events — just the user events that should affect our global state. The AnimalDetail component displays a button to present the AnimalEditor component. This is an example of local component state; we choose to save this state at our component level — not in ImmutableData.

There are two more subtle user events. When our CategoryList will be displayed, we want to fetch our Categories. When our AnimalList will be displayed, we want to fetch our Animals. We choose to transform our global state for efficiency and performance. A user can launch our product and open multiple windows on their macOS desktop. If every window performed an independent fetch, we would be fetching the same data multiple times. Transforming global state means we can keep track of our most recent fetch and prevent unnecessary fetches from consuming system resources.

These Action values tell one side of our story: user events coming from our component tree. There is one more domain we want to support: data events coming from our persistent store. This product will need to support asynchronous operations to save its global state to a persistent store on our filesystem. We’re going to pass operations to our persistent store, wait for a response, and then dispatch an Action value back to our Reducer. In the same way that our “User Interface” domain was for action values that came from our component tree, our “Data” domain is for action values that come from our persistent store. Before we complete this chapter, we will see exactly how User Events are transformed into Data Events. For now, let’s concentrate on just defining what action values our persistent store would need to dispatch to our Reducer.

- The

Categoryvalues were fetched. - The

Animalvalues were fetched. - The Sample Data from first launch was reloaded and the previously stored data was deleted.

- An

Animalvalue was added. - An

Animalvalue was updated. - An

Animalvalue was deleted.

Let’s put these together and see what our Action values look like. Add a new Swift file under Sources/AnimalsData. Name this file AnimalsAction.swift.

Before we start writing code, let’s think a little about our approach to naming these actions. Remember: our goal is to think declaratively. These action values tell our Reducer what just happened — not how it should behave. One convention we adopt in this tutorial is to name our Action values by where they came from. An action from the UI domain indicating that the Category List will be displayed could be named: uiCategoryListOnAppear. This works, but let’s try a slightly different approach. We’re going to model our Action values not as “one big” enum type, but as a set of “nested” enum types. When we build our Reducer, we can see how pattern-matching against these enum types enables a natural pattern of composition to keep code organized.

Let’s start with our domains and then work down to specific actions:

// AnimalsAction.swift

public enum AnimalsAction: Hashable, Sendable {

case ui(_ action: UI)

case data(_ action: Data)

}

Our UI domain will be for action values coming from our component tree. Our Data domain will be for action values coming from our persistent store.

Let’s start with our UI domain. We define four sub-domains under UI: these map to four components.

// AnimalsAction.swift

extension AnimalsAction {

public enum UI: Hashable, Sendable {

case categoryList(_ action: CategoryList)

case animalList(_ action: AnimalList)

case animalDetail(_ action: AnimalDetail)

case animalEditor(_ action: AnimalEditor)

}

}

Under the UI.CategoryList domain, we define two actions: the action for when the component will be displayed, and the action for when the user confirms to reload sample data:

// AnimalsAction.swift

extension AnimalsAction.UI {

public enum CategoryList: Hashable, Sendable {

case onAppear

case onTapReloadSampleDataButton

}

}

Under the UI.AnimalList domain, we define two actions: the action for when the component will be displayed, and the action for when the user confirms to delete an Animal.

// AnimalsAction.swift

extension AnimalsAction.UI {

public enum AnimalList: Hashable, Sendable {

case onAppear

case onTapDeleteSelectedAnimalButton(animalId: Animal.ID)

}

}

The onTapDeleteSelectedAnimalButton passes an Animal.ID as an associated value; without this value, our Reducer would not know which Animal the user just attempted to delete. Associated values can be important tools for passing critical information to your Reducer, but take care to keep these “clean” and avoid passing data that is not necessary to process your action.

Under the UI.AnimalDetail domain, we define one action: the action for when the user confirms to delete an Animal.

// AnimalsAction.swift

extension AnimalsAction.UI {

public enum AnimalDetail: Hashable, Sendable {

case onTapDeleteSelectedAnimalButton(animalId: Animal.ID)

}

}

Under the UI.AnimalEditor domain, we define two actions: the action for when the user confirms to add an Animal, and the action for when the user confirms to update an Animal:

// AnimalsAction.swift

extension AnimalsAction.UI {

public enum AnimalEditor: Hashable, Sendable {

case onTapAddAnimalButton(

id: Animal.ID,

name: String,

diet: Animal.Diet,

categoryId: Category.ID

)

case onTapUpdateAnimalButton(

animalId: Animal.ID,

name: String,

diet: Animal.Diet,

categoryId: Category.ID

)

}

}

Let’s turn our attention to our Data domain. We will define a PersistentSession sub-domain to indicate these actions are from events in the session we use to manage our persistent store:

// AnimalsAction.swift

extension AnimalsAction {

public enum Data: Hashable, Sendable {

case persistentSession(_ action: PersistentSession)

}

}

Here are the six action values we define under Data.PersistentSession:

// AnimalsAction.swift

extension AnimalsAction.Data {

public enum PersistentSession: Hashable, Sendable {

case didFetchCategories(result: FetchCategoriesResult)

case didFetchAnimals(result: FetchAnimalsResult)

case didReloadSampleData(result: ReloadSampleDataResult)

case didAddAnimal(

id: Animal.ID,

result: AddAnimalResult

)

case didUpdateAnimal(

animalId: Animal.ID,

result: UpdateAnimalResult

)

case didDeleteAnimal(

animalId: Animal.ID,

result: DeleteAnimalResult

)

}

}

For every asynchronous operation on our persistent store, we assume that the operation could either succeed or fail. Our associated values will contain valid data when our operation succeeds or an error string when our operation fails. Here are those result types:

// AnimalsAction.swift

extension AnimalsAction.Data.PersistentSession {

public enum FetchCategoriesResult: Hashable, Sendable {

case success(categories: Array<Category>)

case failure(error: String)

}

}

extension AnimalsAction.Data.PersistentSession {

public enum FetchAnimalsResult: Hashable, Sendable {

case success(animals: Array<Animal>)

case failure(error: String)

}

}

extension AnimalsAction.Data.PersistentSession {

public enum ReloadSampleDataResult: Hashable, Sendable {

case success(

animals: Array<Animal>,

categories: Array<Category>

)

case failure(error: String)

}

}

extension AnimalsAction.Data.PersistentSession {

public enum AddAnimalResult: Hashable, Sendable {

case success(animal: Animal)

case failure(error: String)

}

}

extension AnimalsAction.Data.PersistentSession {

public enum UpdateAnimalResult: Hashable, Sendable {

case success(animal: Animal)

case failure(error: String)

}

}

extension AnimalsAction.Data.PersistentSession {

public enum DeleteAnimalResult: Hashable, Sendable {

case success(animal: Animal)

case failure(error: String)

}

}

An alternative approach would be to use [Swift.Result]8 instead of custom types. We build custom types as a convention for our sample products, but we don’t have a very strong opinion about what would be best for your own products; if you prefer to use Swift.Result, you can use Swift.Result. We also take a very “lightweight” approach to error handling in these sample products: our error is just a String value. At production scale, error reporting would probably need to add extra payloads and context for improved debugging.

PersistentSession

Let’s turn our attention to building support for asynchronous operations. Our Animals product will perform asynchronous operations to persist state to the filesystem in a database. We model these operations as thunks.9 Let’s begin with a quick review: here is our Dispatcher protocol from our ImmutableData package:

// Dispatcher.swift

public protocol Dispatcher<State, Action> : Sendable {

associatedtype State : Sendable

associatedtype Action : Sendable

associatedtype Dispatcher : ImmutableData.Dispatcher<Self.State, Self.Action>

associatedtype Selector : ImmutableData.Selector<Self.State>

@MainActor func dispatch(action: Action) throws

@MainActor func dispatch(thunk: @Sendable (Self.Dispatcher, Self.Selector) throws -> Void) rethrows

@MainActor func dispatch(thunk: @Sendable (Self.Dispatcher, Self.Selector) async throws -> Void) async rethrows

}

Our dispatch function supports passing thunk closures. These closures take two arguments: a Dispatcher and a Selector. We will see these closures in action when we build our asynchronous operations to persist state. Let’s begin with a type to return these thunk closures. Add a new Swift file under Sources/AnimalsData. Name this file PersistentSession.swift. Here is the first step:

// PersistentSession.swift

import ImmutableData

public protocol PersistentSessionPersistentStore: Sendable {

func fetchAnimalsQuery() async throws -> Array<Animal>

func addAnimalMutation(

name: String,

diet: Animal.Diet,

categoryId: String

) async throws -> Animal

func updateAnimalMutation(

animalId: String,

name: String,

diet: Animal.Diet,

categoryId: String

) async throws -> Animal

func deleteAnimalMutation(animalId: String) async throws -> Animal

func fetchCategoriesQuery() async throws -> Array<Category>

func reloadSampleDataMutation() async throws -> (

animals: Array<Animal>,

categories: Array<Category>

)

}

final actor PersistentSession<PersistentStore> where PersistentStore : PersistentSessionPersistentStore {

private let store: PersistentStore

init(store: PersistentStore) {

self.store = store

}

}

Our PersistentSession is an actor; this means that we can perform serialized asynchronous operations and deliver thunk closures which are Sendable. We create our PersistentSession instance with a PersistentStore, which is a type that conforms to the PersistentSessionPersistentStore protocol. Our PersistentSessionPersistentStore protocol defines the six operations (two queries and four mutations) we need to perform to keep our state persisted.

Let’s build our first thunk. We begin with fetchAnimalsQuery. This is a thunk that performs an asynchronous fetch from our PersistentStore to fetch an Array of Animal instances.

// PersistentSession.swift

extension PersistentSession {

func fetchAnimalsQuery<Dispatcher, Selector>() -> @Sendable (

Dispatcher,

Selector

) async throws -> Void where Dispatcher : ImmutableData.Dispatcher<AnimalsState, AnimalsAction>, Selector : ImmutableData.Selector<AnimalsState> {

{ dispatcher, selector in

try await self.fetchAnimalsQuery(

dispatcher: dispatcher,

selector: selector

)

}

}

}

extension PersistentSession {

private func fetchAnimalsQuery(

dispatcher: some ImmutableData.Dispatcher<AnimalsState, AnimalsAction>,

selector: some ImmutableData.Selector<AnimalsState>

) async throws {

let animals = try await {

do {

return try await self.store.fetchAnimalsQuery()

} catch {

try await dispatcher.dispatch(

action: .data(

.persistentSession(

.didFetchAnimals(

result: .failure(

error: error.localizedDescription

)

)

)

)

)

throw error

}

}()

try await dispatcher.dispatch(

action: .data(

.persistentSession(

.didFetchAnimals(

result: .success(

animals: animals

)

)

)

)

)

}

}

This might look like a lot of code, but it’s not so difficult if we break things down step-by-step:

- We attempt to run the

fetchAnimalsQueryoperation from ourPersistentStoreinstance. - If the

fetchAnimalsQueryoperation fails, we dispatch afailureaction value to ourdispatcher. In this product, we take a short-cut with our error handling: we only save thelocalizedDescriptionstring value. In a legit production application, this would be an opportunity to pass extra context that would be important for debugging this error at runtime. - If the

fetchAnimalsQueryoperation succeeds, we dispatch asuccessaction value to ourdispatcherwith theArrayofAnimalvalues as an associated value payload.

The closure returned by fetchAnimalsQuery is passed to our Dispatcher. We will see this in our next section when we build our Listener class.

Let’s see a more complex example. Our addAnimalMutation will accept four parameters:

// PersistentSession.swift

extension PersistentSession {

func addAnimalMutation<Dispatcher, Selector>(

id: String,

name: String,

diet: Animal.Diet,

categoryId: String

) -> @Sendable (

Dispatcher,

Selector

) async throws -> Void where Dispatcher : ImmutableData.Dispatcher<AnimalsState, AnimalsAction>, Selector : ImmutableData.Selector<AnimalsState> {

{ dispatcher, selector in

try await self.addAnimalMutation(

dispatcher: dispatcher,

selector: selector,

id: id,

name: name,

diet: diet,

categoryId: categoryId

)

}

}

}

extension PersistentSession {

private func addAnimalMutation(

dispatcher: some ImmutableData.Dispatcher<AnimalsState, AnimalsAction>,

selector: some ImmutableData.Selector<AnimalsState>,

id: String,

name: String,

diet: Animal.Diet,

categoryId: String

) async throws {

let animal = try await {

do {

return try await self.store.addAnimalMutation(

name: name,

diet: diet,

categoryId: categoryId

)

} catch {

try await dispatcher.dispatch(

action: .data(

.persistentSession(

.didAddAnimal(

id: id,

result: .failure(

error: error.localizedDescription

)

)

)

)

)

throw error

}

}()

try await dispatcher.dispatch(

action: .data(

.persistentSession(

.didAddAnimal(

id: id,

result: .success(

animal: animal

)

)

)

)

)

}

}

It looks like a lot of code, but let’s try and break things down step-by-step:

- The

addAnimalMutationthat isprivateis a helper. It accepts six parameters: aDispatcher, aSelector, and the four parameters passed from our component tree (id,name,diet, andcategoryId). We attempt to run theaddAnimalMutationoperation from ourPersistentStoreinstance withname,diet, andcategoryIdas parameters to the mutation. Theidpassed from our component tree is actually a “temp” id. We keep this for tracking a loading status. Our actual persistent store will be responsible for building its ownidproperty on this newAnimalinstance. - If the

addAnimalMutationoperation from ourPersistentStoreinstance fails, we dispatch afailureaction value to ourdispatcherwith theidanderror.localizedDescriptionas associated values. - If the

addAnimalMutationoperation succeeds, we dispatch asuccessaction value to ourdispatcherwith theidandAnimalvalue as associated values. - The

addAnimalMutationthat isinternalaccepts the four parameters passed from our component tree (id,name,diet, andcategoryId) and returns a closure that accepts two parameters: aDispatcher, aSelector. This closure can then be passed to ourDispatcher.

This functional style of programming — where functions return functions — is very common in Redux. The argument could be made that Swift is not a “true” functional programming language,10 but neither would be JavaScript. Like the original engineers behind React and Flux, we can bring ideas and concepts from functional programming to our preferred domain — even if our language is “multi-paradigm” and not exclusively functional.

Let’s continue with updateAnimalMutation:

// PersistentSession.swift

extension PersistentSession {

func updateAnimalMutation<Dispatcher, Selector>(

animalId: String,

name: String,

diet: Animal.Diet,

categoryId: String

) -> @Sendable (

Dispatcher,

Selector

) async throws -> Void where Dispatcher : ImmutableData.Dispatcher<AnimalsState, AnimalsAction>, Selector : ImmutableData.Selector<AnimalsState> {

{ dispatcher, selector in

try await self.updateAnimalMutation(

dispatcher: dispatcher,

selector: selector,

animalId: animalId,

name: name,

diet: diet,

categoryId: categoryId

)

}

}

}

extension PersistentSession {

private func updateAnimalMutation(

dispatcher: some ImmutableData.Dispatcher<AnimalsState, AnimalsAction>,

selector: some ImmutableData.Selector<AnimalsState>,

animalId: String,

name: String,

diet: Animal.Diet,

categoryId: String

) async throws {

let animal = try await {

do {

return try await self.store.updateAnimalMutation(

animalId: animalId,

name: name,

diet: diet,

categoryId: categoryId

)

} catch {

try await dispatcher.dispatch(

action: .data(

.persistentSession(

.didUpdateAnimal(

animalId: animalId,

result: .failure(

error: error.localizedDescription

)

)

)

)

)

throw error

}

}()

try await dispatcher.dispatch(

action: .data(

.persistentSession(

.didUpdateAnimal(

animalId: animalId,

result: .success(

animal: animal

)

)

)

)

)

}

}

This should look familiar: we pass four parameters to our PersistentStore to update an Animal in our database. We dispatch a failure action when an error is thrown and we dispatch a success action when our updated Animal is returned.

Here is deleteAnimalMutation:

// PersistentSession.swift

extension PersistentSession {

func deleteAnimalMutation<Dispatcher, Selector>(

animalId: String

) -> @Sendable (

Dispatcher,

Selector

) async throws -> Void where Dispatcher : ImmutableData.Dispatcher<AnimalsState, AnimalsAction>, Selector : ImmutableData.Selector<AnimalsState> {

{ dispatcher, selector in

try await self.deleteAnimalMutation(

dispatcher: dispatcher,

selector: selector,

animalId: animalId

)

}

}

}

extension PersistentSession {

private func deleteAnimalMutation(

dispatcher: some ImmutableData.Dispatcher<AnimalsState, AnimalsAction>,

selector: some ImmutableData.Selector<AnimalsState>,

animalId: String

) async throws {

let animal = try await {

do {

return try await self.store.deleteAnimalMutation(

animalId: animalId

)

} catch {

try await dispatcher.dispatch(

action: .data(

.persistentSession(

.didDeleteAnimal(

animalId: animalId,

result: .failure(

error: error.localizedDescription

)

)

)

)

)

throw error

}

}()

try await dispatcher.dispatch(

action: .data(

.persistentSession(

.didDeleteAnimal(

animalId: animalId,

result: .success(

animal: animal

)

)

)

)

)

}

}

Again, this looks like a lot of code, but we can think through things step-by-step. We await an operation on our PersistentStore database. We then dispatch a failure action when an error is thrown and we dispatch a success action when our Animal is deleted.

Here is fetchCategoriesQuery:

// PersistentSession.swift

extension PersistentSession {

func fetchCategoriesQuery<Dispatcher, Selector>() -> @Sendable (

Dispatcher,

Selector

) async throws -> Void where Dispatcher : ImmutableData.Dispatcher<AnimalsState, AnimalsAction>, Selector : ImmutableData.Selector<AnimalsState> {

{ dispatcher, selector in

try await self.fetchCategoriesQuery(

dispatcher: dispatcher,

selector: selector

)

}

}

}

extension PersistentSession {

private func fetchCategoriesQuery(

dispatcher: some ImmutableData.Dispatcher<AnimalsState, AnimalsAction>,

selector: some ImmutableData.Selector<AnimalsState>

) async throws {

let categories = try await {

do {

return try await self.store.fetchCategoriesQuery()

} catch {

try await dispatcher.dispatch(

action: .data(

.persistentSession(

.didFetchCategories(

result: .failure(

error: error.localizedDescription

)

)

)

)

)

throw error

}

}()

try await dispatcher.dispatch(

action: .data(

.persistentSession(

.didFetchCategories(

result: .success(

categories: categories

)

)

)

)

)

}

}

Here is reloadSampleDataMutation:

// PersistentSession.swift

extension PersistentSession {

func reloadSampleDataMutation<Dispatcher, Selector>() -> @Sendable (

Dispatcher,

Selector

) async throws -> Void where Dispatcher : ImmutableData.Dispatcher<AnimalsState, AnimalsAction>, Selector : ImmutableData.Selector<AnimalsState> {

{ dispatcher, selector in

try await self.reloadSampleDataMutation(

dispatcher: dispatcher,

selector: selector

)

}

}

}

extension PersistentSession {

private func reloadSampleDataMutation(

dispatcher: some ImmutableData.Dispatcher<AnimalsState, AnimalsAction>,

selector: some ImmutableData.Selector<AnimalsState>

) async throws {

let (animals, categories) = try await {

do {

return try await self.store.reloadSampleDataMutation()

} catch {

try await dispatcher.dispatch(

action: .data(

.persistentSession(

.didReloadSampleData(

result: .failure(

error: error.localizedDescription

)

)

)

)

)

throw error

}

}()

try await dispatcher.dispatch(

action: .data(

.persistentSession(

.didReloadSampleData(

result: .success(

animals: animals,

categories: categories

)

)

)

)

)

}

}

We did write a fair amount of code, but we see that these functions are not as complex as they might seem. Our PersistentSession actor builds the thunk functions we need to pass to our Dispatcher. At this point, our PersistentSession does not know much about the implementation details of our PersistentStore type; this dependency is generic by design. We’ll come back to this later and build a concrete PersistentStore type before our chapter is complete.

Listener

When we built ImmutableUI.Listener, we created a type that could perform work when Action values were dispatched to our Store. We’re going to see what a Listener looks like for a product domain. This Listener type will be specific to our product; it will know about Animal and Category and the specific domain this product is built on. When actions are dispatched to our Store, we will then use our Listener — together with our PersistentSession — to perform asynchronous operations. Our Listener receives Action values after our Reducer has returned; but we can think of these two types “working together” to affect State transformations in our product. When an Action value is dispatched to our Store, our Reducer synchronously performs transformations on State. Our Listener then has the opportunity to use that Action value to begin asynchronous operations, which could then dispatch new Action values that affect more transformations on State.

Let’s see this in action. Add a new Swift file under Sources/AnimalsData. Name this file Listener.swift. Here is our main declaration:

// Listener.swift

import Foundation

import ImmutableData

@MainActor final public class Listener<PersistentStore> where PersistentStore : PersistentSessionPersistentStore {

private let session: PersistentSession<PersistentStore>

private weak var store: AnyObject?

private var task: Task<Void, any Error>?

public init(store: PersistentStore) {

self.session = PersistentSession(store: store)

}

deinit {

self.task?.cancel()

}

}

Our Listener class accepts a PersistentStore instance on creation. We save a PersistentSession as an instance property created from the PersistentStore parameter. Our Listener will begin listening to an ImmutableData.Streamer. We make our Listener a MainActor type to match the declarations on ImmutableData.Streamer.

Here is our declaration to begin listening for Action values:

// Listener.swift

extension UserDefaults {

fileprivate var isDebug: Bool {

self.bool(forKey: "com.northbronson.AnimalsData.Debug")

}

}

extension Listener {

public func listen(to store: some ImmutableData.Dispatcher<AnimalsState, AnimalsAction> & ImmutableData.Selector<AnimalsState> & ImmutableData.Streamer<AnimalsState, AnimalsAction> & AnyObject) {

if self.store !== store {

self.store = store

let stream = store.makeStream()

self.task?.cancel()

self.task = Task { [weak self] in

for try await (oldState, action) in stream {

#if DEBUG

if UserDefaults.standard.isDebug {

print("[AnimalsData][Listener] Old State: \(oldState)")

print("[AnimalsData][Listener] Action: \(action)")

print("[AnimalsData][Listener] New State: \(store.state)")

}

#endif

guard let self = self else { return }

await self.onReceive(from: store, oldState: oldState, action: action)

}

}

}

}

}

Our listen function takes a Store as a parameter. This Store is generic and adopts the important protocols we need to support our Listener. We save the Store to an instance property and begin a stream. We then save a task to an instance property and begin to await on that stream. The stream returns tuple values: a State indicating the previous state of our system and an Action indicating the Action that was just dispatched.

To share information for debugging, we add optional print statements in debug builds. Being able to see the previous and current states of our system on every Action value can be important when trying to debug unexpected behaviors in our product. Similar to ImmutableUI.AsyncListener, we add a custom key on UserDefaults for enabling this logging.

We then forward the store, the oldState, and the action to a new function. Here’s what that looks like:

// Listener.swift

extension Listener {

private func onReceive(

from store: some ImmutableData.Dispatcher<AnimalsState, AnimalsAction> & ImmutableData.Selector<AnimalsState>,

oldState: AnimalsState,

action: AnimalsAction

) async {

switch action {

case .ui(action: let action):

await self.onReceive(from: store, oldState: oldState, action: action)

default:

break

}

}

}

For our Listener, we don’t need to perform asynchronous operations when our PersistentSession dispatches Action values; it’s the other way around. When our component tree dispatches Action values, we read those values — after our Reducer has returned — and then begin our asynchronous operations on PersistentSession.

We can break over all the Action values that are not from the AnimalsAction.UI domain. For now, we only care about acting on the values from AnimalsAction.UI. Here is our next function:

// Listener.swift

extension Listener {

private func onReceive(

from store: some ImmutableData.Dispatcher<AnimalsState, AnimalsAction> & ImmutableData.Selector<AnimalsState>,

oldState: AnimalsState,

action: AnimalsAction.UI

) async {

switch action {

case .categoryList(action: let action):

await self.onReceive(from: store, oldState: oldState, action: action)

case .animalList(action: let action):

await self.onReceive(from: store, oldState: oldState, action: action)

case .animalDetail(action: let action):

await self.onReceive(from: store, oldState: oldState, action: action)

case .animalEditor(action: let action):

await self.onReceive(from: store, oldState: oldState, action: action)

}

}

}

As an engineering convention and style, we scope our Listener down by action domains. This code isn’t really needed; we could just do this in “one big” switch statement, but this approach lets us focus on composing smaller functions together. You can choose to follow this convention in your own products.

We now need four small functions to process action values across our AnimalsAction.UI domain. Here is AnimalsAction.UI.CategoryList:

// Listener.swift

extension Listener {

private func onReceive(

from store: some ImmutableData.Dispatcher<AnimalsState, AnimalsAction> & ImmutableData.Selector<AnimalsState>,

oldState: AnimalsState,

action: AnimalsAction.UI.CategoryList

) async {

switch action {

case .onAppear:

if oldState.categories.status == nil,

store.state.categories.status == .waiting {

do {

try await store.dispatch(

thunk: self.session.fetchCategoriesQuery()

)

} catch {

print(error)

}

}

case .onTapReloadSampleDataButton:

if oldState.categories.status != .waiting,

store.state.categories.status == .waiting,

oldState.animals.status != .waiting,

store.state.animals.status == .waiting {

do {

try await store.dispatch(

thunk: self.session.reloadSampleDataMutation()

)

} catch {

print(error)

}

}

}

}

}

There are two Action values under the AnimalsAction.UI.CategoryList domain. Let’s begin with onAppear. We will dispatch onAppear when our CategoryList is ready to display. Our goal is for this value to then begin an asynchronous operation to fetch Category values. For performance, we want to only perform that fetch once: we do not plan to “re-fetch” the second time the CategoryList is ready to display.

At this point, we already know a lot about the state of our system at the time this Action value was dispatched: we know the previous state of our system, we know the Action value, and we also have the ability to quickly find the current state of our system. This function receives its values after the Reducer has returned. Because store adopts ImmutableData.Selector, we can easily ask for store.state to know how our Reducer has transformed the previous state of our system.

When a CategoryList is ready to display, we begin by checking if the oldState.categories.status is nil. We expect this to indicate that a fetch has not been attempted; the next fetch will be our first. Next, we check if store.state.categories.status is waiting. We expect this to indicate that a fetch should be attempted.

If our system has transitioned from a categories.status equal to nil to categories.status equal to waiting, this implies that we are going to begin our initial fetch. We dispatch the fetchCategoriesQuery thunk we built in our previous section. In the event of an error, we log the error to print. In a production application, you should improve error handling and reporting. For the purposes of our tutorial, we will try to keep our focus on the ImmutableData architecture; you should explore error handling in a way that makes the most sense for your team and your product.

For onTapReloadSampleDataButton, we perform a similar operation. We can begin by checking if we are already waiting for a fetch to complete. If we are not waiting for a fetch to complete, we begin a new one. Unlike onAppear, we do want our user to have the option to dispatch this operation more than once. We perform this check against our Categories and Animals domains, then set both domains to waiting to indicate there is an active fetch.

That’s the basic idea of our Listener. We receive Action values after our Reducer has returned, and then have the option to perform asynchronous operations on our PersistentSession based on the state of our system.

Here is our AnimalList domain:

// Listener.swift

extension Listener {

private func onReceive(

from store: some ImmutableData.Dispatcher<AnimalsState, AnimalsAction> & ImmutableData.Selector<AnimalsState>,

oldState: AnimalsState,

action: AnimalsAction.UI.AnimalList

) async {

switch action {

case .onAppear:

if oldState.animals.status == nil,

store.state.animals.status == .waiting {

do {

try await store.dispatch(

thunk: self.session.fetchAnimalsQuery()

)

} catch {

print(error)

}

}

case .onTapDeleteSelectedAnimalButton(animalId: let animalId):

if oldState.animals.queue[animalId] != .waiting,

store.state.animals.queue[animalId] == .waiting {

do {

try await store.dispatch(

thunk: self.session.deleteAnimalMutation(animalId: animalId)

)

} catch {

print(error)

}

}

}

}

}

Our onAppear action value follows a similar pattern to CategoryList: if we transitioned from status equals nil to status equals waiting, then we dispatch a fetchAnimalsQuery thunk.

Our onTapDeleteSelectedAnimalButton should begin if we are not already waiting on an operation for this Animal. We check to see if the Status value saved for this Animal.ID transitioned to waiting before we dispatch our deleteAnimalMutation thunk.

Here is our AnimalDetail domain performing a similar dispatch to deleteAnimalMutation:

// Listener.swift

extension Listener {

private func onReceive(

from store: some ImmutableData.Dispatcher<AnimalsState, AnimalsAction> & ImmutableData.Selector<AnimalsState>,

oldState: AnimalsState,

action: AnimalsAction.UI.AnimalDetail

) async {

switch action {

case .onTapDeleteSelectedAnimalButton(animalId: let animalId):

if oldState.animals.queue[animalId] != .waiting,

store.state.animals.queue[animalId] == .waiting {

do {

try await store.dispatch(

thunk: self.session.deleteAnimalMutation(animalId: animalId)

)

} catch {

print(error)

}

}

}

}

}

Here is our AnimalEditor domain:

// Listener.swift

extension Listener {

private func onReceive(

from store: some ImmutableData.Dispatcher<AnimalsState, AnimalsAction> & ImmutableData.Selector<AnimalsState>,

oldState: AnimalsState,

action: AnimalsAction.UI.AnimalEditor

) async {

switch action {

case .onTapAddAnimalButton(id: let id, name: let name, diet: let diet, categoryId: let categoryId):

if oldState.animals.queue[id] != .waiting,

store.state.animals.queue[id] == .waiting {

do {

try await store.dispatch(

thunk: self.session.addAnimalMutation(id: id, name: name, diet: diet, categoryId: categoryId)

)

} catch {

print(error)

}

}

case .onTapUpdateAnimalButton(animalId: let animalId, name: let name, diet: let diet, categoryId: let categoryId):

if oldState.animals.queue[animalId] != .waiting,

store.state.animals.queue[animalId] == .waiting {

do {

try await store.dispatch(

thunk: self.session.updateAnimalMutation(animalId: animalId, name: name, diet: diet, categoryId: categoryId)

)

} catch {

print(error)

}

}

}

}

}

This should look familiar: we check if the Status of the Animal value we are interested in just transitioned to waiting; this indicates we are ready to dispatch our thunk operation.

Our Listener will be created on app launch at the same time we create our Store. Our Listener is built for receiving action values, but you can think creatively about more use cases. Think about situations that need to receive events over time. We could build a PushListener that is designed to receive push notification payloads from Apple. We could build a WebSocketListener that is designed to receive web-socket data from our server. We could build a AppIntentListener or WidgetListener that is designed to listen to events from our system. These are outside the scope of this tutorial, but these Listener classes can be composed together in powerful ways when building complex products.

AnimalsReducer

For our previous product, our CounterReducer was a synchronous function without any side effects. Operating under those same constraints, our Animals product also needs to accommodate asynchronously fetching from and writing to a persistent store on our filesystem. We’re going to build a Reducer that operates under the constraints of our ImmutableData architecture; we will see how this fits together with our Listener class to handle side effects.

Our CounterReducer was one switch statement. Since our CounterAction was only two case values, this was easy. In complex products, the set of Action values can grow to the point that one big switch statement is no longer easy: we want a way to break this work into smaller pieces. We will see a few techniques that can help when you scale your own products to many Action values.

Add a new Swift file under Sources/AnimalsData. Name this file AnimalsReducer.swift. Here is the first reduce function:

// AnimalsReducer.swift

public enum AnimalsReducer {

@Sendable public static func reduce(

state: AnimalsState,

action: AnimalsAction

) throws -> AnimalsState {

switch action {

case .ui(action: let action):

return try self.reduce(state: state, action: action)

case .data(action: let action):

return try self.reduce(state: state, action: action)

}

}

}

Our reduce function takes an AnimalsState and an AnimalsAction as parameters. The return value is an AnimalsState. Our reduce function also throws errors. We switch over the Action value. Our case statements then forwards the Action value to two new reduce functions (which we will build in our next step). This “pattern-matching” allows us one way to scope and compose together small functions; it’s an alternative to putting everything in one big reduce function. Our root reduce function forwards actions from the AnimalsAction.UI domain to the AnimalsAction.UI reducer and actions from the AnimalsAction.Data domain to the AnimalsAction.Data reducer.

Let’s build our next reduce function. This is the function that accepts a AnimalsAction.UI value:

// AnimalsReducer.swift

extension AnimalsReducer {

private static func reduce(

state: AnimalsState,

action: AnimalsAction.UI

) throws -> AnimalsState {

switch action {

case .categoryList(action: let action):

return try self.reduce(state: state, action: action)

case .animalList(action: let action):

return try self.reduce(state: state, action: action)

case .animalDetail(action: let action):

return try self.reduce(state: state, action: action)

case .animalEditor(action: let action):

return try self.reduce(state: state, action: action)

}

}

}

Here, we perform another dimension of pattern-matching: this function knows that its Action value is scoped to the AnimalsAction.UI domain. We then forward each of those sub-domains to a new reduce function.

Here is our reduce function scoped to the AnimalsAction.UI.CategoryList domain:

// AnimalsReducer.swift

extension AnimalsReducer {

private static func reduce(

state: AnimalsState,

action: AnimalsAction.UI.CategoryList

) throws -> AnimalsState {

switch action {

case .onAppear:

if state.categories.status == nil {

var state = state

state.categories.status = .waiting

return state

}

return state

case .onTapReloadSampleDataButton:

if state.categories.status != .waiting,

state.animals.status != .waiting {

var state = state

state.categories.status = .waiting

state.animals.status = .waiting

return state

}

return state

}

}

}

Our AnimalsAction.UI.CategoryList domain is a “leaf”; switching over the Action value does not produce additional sub-domains. This is our opportunity to transform our State.

We begin with onAppear. This value indicates the CategoryList component will display. This is when we would like to begin an asynchronous fetch of our Category values from our persistent store. We are blocked on asynchronous side effects in a Reducer. Our solution is to transform our State to indicate that we should fetch. If the status of the most recent fetch is nil, we set the status of categories to waiting. When we return from our Reducer, our Listener will receive the same State and Action values that were passed to our Reducer. Our Listener will then perform the asynchronous operation to fetch Category values.

Remember, our Reducer is not for performing asynchronous operations or side effects. Our Reducer is for performing synchronous operations without side effects. Our Reducer will transform our State in an appropriate way such that our Listener will then perform its asynchronous operations. This is an important concept we will see many times before our tutorial is complete.

Our onTapReloadSampleDataButton value is dispatched when a user has confirmed they wish to reload the sample data from initial launch. We set the status of our categories and our animals to waiting — after confirming we are not already waiting — to indicate we should fetch both domains. The State and Action will then forward to our Listener class for us to perform our asynchronous side effects. Remember, all we do for our reduce function is set the correct flags for our Listener.

Let’s build a Reducer for our UI.AnimalList domain:

// AnimalsReducer.swift

extension AnimalsReducer {

package struct Error: Swift.Error {

package enum Code: Hashable, Sendable {

case animalNotFound

}

package let code: Self.Code

}

}

extension AnimalsState {

fileprivate func onTapDeleteSelectedAnimalButton(animalId: Animal.ID) throws -> Self {

guard let _ = self.animals.data[animalId] else {

throw AnimalsReducer.Error(code: .animalNotFound)

}

var state = self

state.animals.queue[animalId] = .waiting

return state

}

}

extension AnimalsReducer {

private static func reduce(

state: AnimalsState,

action: AnimalsAction.UI.AnimalList

) throws -> AnimalsState {

switch action {

case .onAppear:

if state.animals.status == nil {

var state = state

state.animals.status = .waiting

return state

}

return state

case .onTapDeleteSelectedAnimalButton(animalId: let animalId):

return try state.onTapDeleteSelectedAnimalButton(animalId: animalId)

}

}

}

Our onAppear value performs similar work to what we saw from CategoryList. Our onTapDeleteSelectedAnimalButton value begins by confirming the Animal.ID is valid: an Animal instance exists for this Animal.ID. If no Animal instance is found, we throw an error. If we did find an Animal instance, we set a Status of waiting on our queue to indicate there is an asynchronous operation taking place on the Animal value.

Our onAppear logic appears “inline”: it’s right under our case statement. Our onTapDeleteSelectedAnimalButton logic appears in a helper function defined on AnimalsState. For simple logic that may only need to be defined in one place, writing it directly under your case statement might work best for you. For more complex logic, or logic that might be duplicated across multiple Action values, factoring that logic out to a helper function might be the best choice.

Let’s build a Reducer for our UI.AnimalDetail domain:

// AnimalsReducer.swift

extension AnimalsReducer {

private static func reduce(

state: AnimalsState,

action: AnimalsAction.UI.AnimalDetail

) throws -> AnimalsState {

switch action {

case .onTapDeleteSelectedAnimalButton(animalId: let animalId):

return try state.onTapDeleteSelectedAnimalButton(animalId: animalId)

}

}

}

You can see why it is convenient to factor logic out of individual case statements: both of these Action values should map to the same transformation on our State.

A legit question here is why are we choosing to define two different Action values. Is the onTapDeleteSelectedAnimalButton value one action that happens from two different components, or is it two actions that happen from two different components?

In larger applications built from Flux and Redux, it is common to “reuse” action values across components. Two different components might display a Delete Animal button that dispatch the same action value. This is not an abuse of the architecture — this is ok.

For our tutorial, we continue with the convention that we name actions by the component where they happened from. We don’t have a strong opinion about whether or not your own products should follow this convention, but we have some reasons for preferring this approach in our tutorials. One of the biggest skills we want engineers to practice is thinking declaratively. For engineers with experience building SwiftUI and SwiftData together, the natural instinct might be to tightly couple presentational component logic — which is declarative — with the imperative mutations needed to transform their global state. This is a very different approach from what we teach in ImmutableData. Your component tree should declaratively dispatch action values on important user events. Your component tree should not be thinking about how this action value will transform state; your component tree should be thinking about communicating what just happened.

In complex products, you might map multiple component user events to just one action value. You must continue to think of your action value as a declarative event — not an imperative instruction. If you introduce an implicit “mental map” where multiple components dispatch one action value, that mental map should continue to tell the infra what happened — not how it should handle that event. If you try to map multiple components to one action value, and your action value subtly — or not so subtly — begins to look like an imperative instruction, slow down and think through what exactly this action value is communicating.

With more experience, engineers learn more about how to “feel” when action values skew too far in the direction of imperative thinking. For our tutorial, we attempt to help enforce declarative thinking. Naming action values after the component where they happened is an attempt to help teach this concept. If this convention works for you and is appropriate for your own products, you can bring this convention with you after our tutorial is complete.

Here is our UI.AnimalEditor domain reducer:

// AnimalsReducer.swift

extension AnimalsState {

fileprivate func onTapAddAnimalButton(

id: Animal.ID,

name: String,

diet: Animal.Diet,

categoryId: String

) -> Self {

var state = self

state.animals.queue[id] = .waiting

return state

}

}

extension AnimalsState {

fileprivate func onTapUpdateAnimalButton(

animalId: Animal.ID,

name: String,

diet: Animal.Diet,

categoryId: Category.ID

) throws -> Self {

guard let _ = self.animals.data[animalId] else {

throw AnimalsReducer.Error(code: .animalNotFound)

}

var state = self

state.animals.queue[animalId] = .waiting

return state

}

}

extension AnimalsReducer {

private static func reduce(

state: AnimalsState,

action: AnimalsAction.UI.AnimalEditor

) throws -> AnimalsState {

switch action {

case .onTapAddAnimalButton(id: let id, name: let name, diet: let diet, categoryId: let categoryId):

return state.onTapAddAnimalButton(id: id, name: name, diet: diet, categoryId: categoryId)

case .onTapUpdateAnimalButton(animalId: let animalId, name: let name, diet: let diet, categoryId: let categoryId):

return try state.onTapUpdateAnimalButton(animalId: animalId, name: name, diet: diet, categoryId: categoryId)

}

}

}

Our onTapAddAnimalButton action sets a Status of waiting on our queue for the id passed in as a temporary id. This will not be the same id once our Animal instance has been created from our PersistentStore; it is just for keeping track of the Status of this operation. Our onTapUpdateAnimalButton action throws an error if the Animal.ID is not found in our State. If the Animal.ID was found, we set a Status of waiting on our queue for this id.

These two functions on AnimalsState are only going to be used one place. Because this logic would not need to be duplicated across multiple case statements, you might choose to write this inline. Try to find the correct balance for code that is easy to read and easy to maintain for your product.

Let’s try building a AnimalsAction.Data Reducer with a slightly different approach:

// AnimalsReducer.swift